A Need for Open Standards in Nanosatellite Development

Blackwing Space is building the LEGO Blocks for Space

The small satellite industry stands at a crossroads. On one side lies a future where nanosatellites remain boutique, custom-engineered systems that take years to develop and cost hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars, accessible only to well-funded institutions and companies. On the other side lies a vision where building satellites becomes more like assembling LEGO blocks - where standardized, interoperable components from different vendors snap together reliably, where software modules can be swapped and upgraded easily, and where the entire industry moves faster because everyone isn't constantly reinventing the same wheels. The path to this second future runs directly through open standards, and at Blackwing Space, we believe that driving adoption and evolution of these standards isn't just good practice but an existential necessity for democratizing access to space.

The Fragmentation Problem: What Happens Without Standards

To understand why open standards matter so profoundly in nanosatellite development, consider what happens in their absence. When every company develops proprietary interfaces, communication protocols, and mechanical designs that work only within its own ecosystem, several problems emerge that compound over time. Each new satellite development team faces essentially the same technical challenges that hundreds of teams before them have already solved—designing power distribution systems, implementing attitude control algorithms, establishing ground communication protocols, and integrating sensors with onboard computers. Without shared standards, each team solves these problems independently, often producing solutions that are incompatible with others'.

This fragmentation creates enormous inefficiency at the industry level. A university developing its first CubeSat cannot simply purchase a proven attitude determination and control system from one vendor, a communications module from another, and a power system from a third, then expect these subsystems to work together seamlessly. Instead, they either build everything themselves, dramatically increasing development time and risk, or they commit to a single vendor's ecosystem, losing flexibility and often paying premium prices for the lock-in. The vendor who sold them the flight computer has little incentive to ensure their product works well with competitors' radio systems, and so integration becomes a custom engineering project requiring deep expertise that many teams simply don't have.

The consequences extend beyond just development inefficiency. When each satellite system is a custom integration of incompatible components, it becomes nearly impossible to build a robust secondary market for spacecraft subsystems, to develop common testing frameworks that reduce qualification costs, or to create shared ground station infrastructure that can communicate with diverse satellite designs using predictable protocols. The industry fragments into isolated silos, each reinventing solutions to identical problems while innovation that could benefit everyone remains locked within proprietary systems.

Understanding Open Standards: More Than Just Documentation

Before we can advocate effectively for open standards, we need to understand what makes a standard truly "open" and why that openness matters. A standard is fundamentally a shared agreement about how something should work—whether that's the physical dimensions of a spacecraft interface, the voltage levels on a data bus, the packet structure for telemetry transmission, or the API that software uses to control a camera. Standards become "open" when these agreements are publicly documented, freely available for anyone to implement, developed through inclusive processes that welcome broad participation, and not encumbered by licensing restrictions that prevent use or modification.

The power of open standards comes from network effects and community dynamics that are impossible to achieve with proprietary approaches. When a standard is open, multiple vendors can implement it independently, creating competition that drives down costs and spurs innovation while maintaining interoperability. Universities and research institutions can adopt the standard without negotiating commercial licenses, enabling educational missions that build the next generation's expertise. Startups can enter the market offering specialized components that plug into the standard ecosystem, rather than needing to provide complete end-to-end solutions to be viable. The standard itself can evolve through community input, incorporating lessons learned across many implementations rather than being constrained by a single company's perspective and priorities.

The CubeSat industry has seen this dynamic play out dramatically with the CubeSat Design Specification, which defined the now-ubiquitous unit sizes and deployer interfaces. By making these specifications open and freely available, the creators enabled an explosion of innovation where launch vehicle providers could build standard deployers knowing that satellites from diverse sources would fit, component vendors could design boards optimized for specific form factors, and satellite developers could focus on their unique mission requirements rather than negotiating custom launch integration for each mission. This single set of open standards arguably enabled the entire small satellite revolution by creating a common language and set of expectations that allowed the ecosystem to develop coherently.

The Current State: Progress and Critical Gaps

The nanosatellite community has made significant progress in establishing open standards over the past two decades, but the landscape remains incomplete, creating ongoing friction and limiting what's possible. The CubeSat Design Specification, now formalized as ISO 21980, provides the foundational standard for physical dimensions and deployer interfaces, ensuring that a 3U CubeSat built in Tennessee will fit in the same deployer as one built in California or Germany. This physical standardization extends to mounting hole patterns, center-of-gravity requirements, and separation switch locations, creating genuine interoperability at the mechanical level.

For data handling and communication, the Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems provides robust, well-tested packet protocols that many satellites use to structure their telemetry and command systems. CCSDS standards have the advantage of extensive flight heritage from large spacecraft programs, and their adoption in small satellites brings proven reliability and interoperability with ground systems that already speak these protocols. Similarly, the European Cooperation for Space Standardization offers frameworks for software development, testing, and quality assurance that help smaller teams adopt practices refined through decades of European space programs.

Open-source hardware initiatives like OreSat and LibreCube have pushed standards deeper into actual implementations, providing not just specifications but complete reference designs that teams can use as starting points. These projects demonstrate how standardized internal buses like SpaceCAN can create reliable communication architectures within spacecraft, while initiatives like SatCat5 show how Ethernet-based approaches can provide high-throughput, low-power device interconnection using familiar networking concepts.

However, critical gaps remain that prevent the full realization of a truly modular, LEGO-like satellite development ecosystem. The most glaring example is the PC/104 form factor, which has become ubiquitous in CubeSat electronics. While PC/104 standardizes the physical board size and the connector locations, it critically fails to standardize the actual pinouts and electrical interfaces. This means that while boards from different vendors physically fit together and can stack mechanically, they often cannot actually communicate or share power without custom adapter boards or cable harnesses. A payload board from one manufacturer cannot simply plug into a flight computer from another and expect to work—each combination requires engineering effort to map signals, resolve voltage incompatibilities, and write custom drivers.

This pinout fragmentation undermines much of the value that a form-factor standard should provide. It's analogous to having USB connectors that are all the same physical shape but where different manufacturers wire the data lines to different pins, requiring custom cables for each device combination. The result is that while the small satellite industry appears to have standardized around PC/104, the reality is a proliferation of incompatible implementations that create exactly the integration challenges that standards are meant to prevent.

Why This Matters Now: The Inflection Point

The urgency around open standards in nanosatellite development isn't abstract or academic but tied directly to where the industry stands today. We're experiencing an inflection point where small satellites are transitioning from primarily educational and experimental platforms to mission-critical infrastructure for communications, Earth observation, scientific research, and national security applications. This transition fundamentally changes what's required from the technology.

When CubeSats were primarily university educational projects with expected lifetimes measured in months and success rates around fifty percent, the custom integration approach was acceptable because the stakes were relatively low and learning was often more important than mission success. But as commercial constellations deploy hundreds or thousands of small satellites, government agencies rely on nanosatellites for operational missions, and multi-million-dollar payloads fly on small spacecraft platforms, the industry can no longer tolerate the inefficiency, risk, and limited scalability that come from fragmented, proprietary approaches.

The economic dynamics also create pressure toward standardization. At Blackwing Space, our business model depends on achieving dramatic cost reductions compared to traditional smallsat platforms—we're targeting fifty to eighty percent cost reductions through lean sourcing and modular reuse. Those kinds of cost improvements are simply impossible if every satellite requires custom integration of unique components. We need to be able to design our platform once, validate it thoroughly, and then produce it in volume with high confidence that each unit will work the same way. We need customers to be able to select payload modules from various vendors and integrate them without requiring our engineering team to do custom work for each configuration. This kind of modularity and reuse only works when there are robust standards defining the interfaces between components.

The supply chain dimension reinforces this urgency. Our emphasis on American-made, automotive-grade components creates opportunities to leverage the massive scale and maturity of the automotive electronics industry, but only if we can establish clear interface standards that let us integrate these components into spacecraft systems reliably. The automotive industry itself learned decades ago that open standards for buses like CAN and LIN, for diagnostic interfaces like OBD-II, and for physical connectors were essential to enable the complex supply chains that modern vehicles require. Space needs to learn the same lesson.

Blackwing's Commitment: Open Standards as Core Architecture

At Blackwing Space, our commitment to open standards isn't a nice-to-have feature or marketing positioning but a fundamental architectural principle that shapes how we design our platforms and structure our business. Our Core Concepts document explicitly calls out "Open-Standards Architecture" as one of our defining characteristics, emphasizing that we build on shared standards for interoperability and extensibility specifically to ensure compatibility with third-party partners, integrators, and downstream analytics platforms.

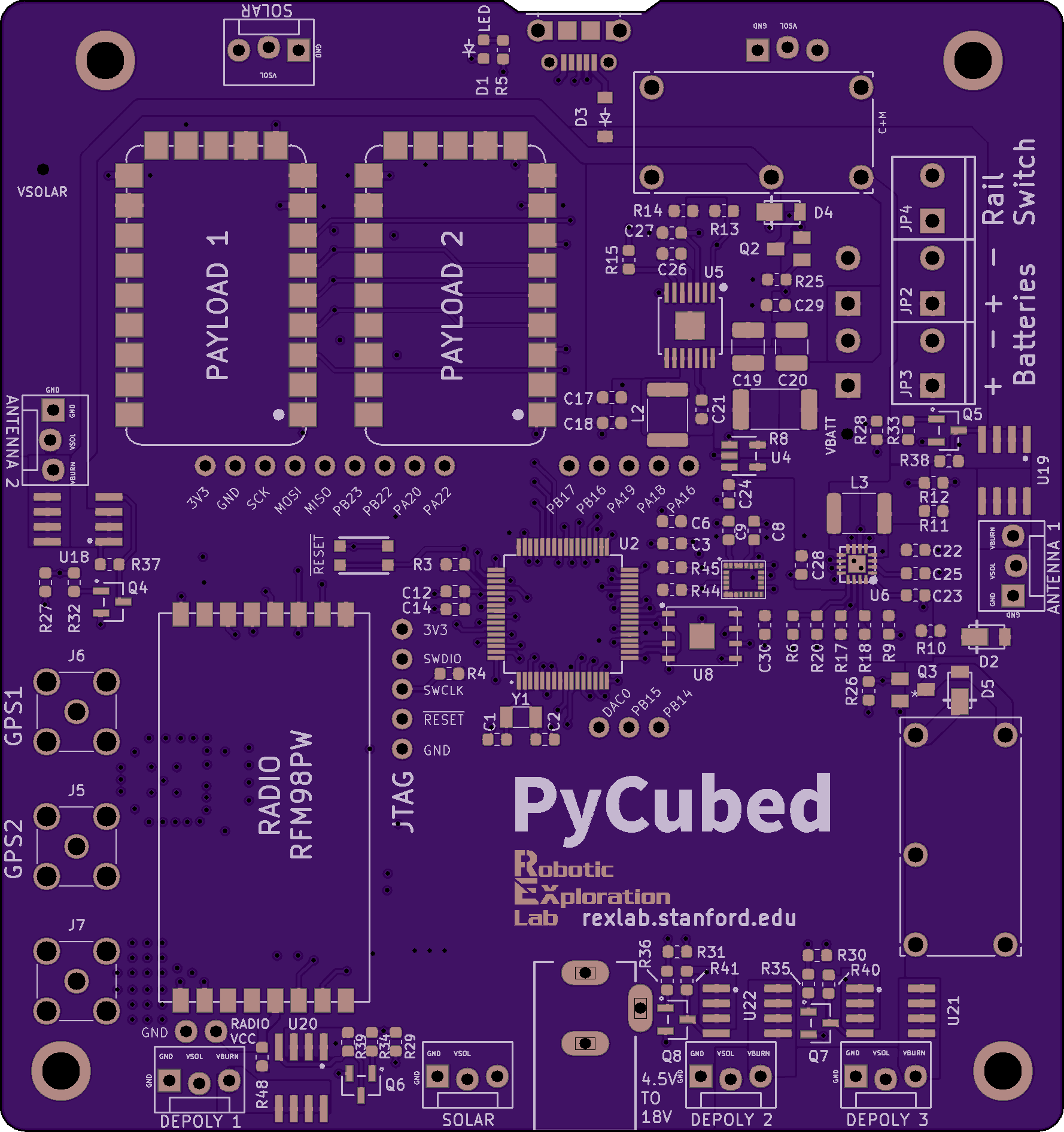

This commitment manifests in concrete ways throughout our technology stack. Our Rook onboard computer is based on PyCubed, an open-source flight computer design that has significant flight heritage and a strong development community. By building on this open foundation rather than developing a completely proprietary flight computer, we benefit from the community's collective experience, can contribute improvements back that benefit everyone, and ensure that customers who understand PyCubed can immediately work with our systems without learning entirely new architectures.

Our modular payload architecture follows open CubeSat-like standards specifically to support plug-and-play payload modules from various sources. Rather than requiring payloads to be explicitly designed for Blackwing spacecraft, we want any payload that follows standard mechanical and electrical interfaces to integrate cleanly with our platforms. This approach maximizes mission flexibility for customers and creates opportunities for payload developers to serve markets beyond just Blackwing satellites.

We're also committed to open data and API support, providing SDKs and API endpoints for telemetry, control, and integration with third-party systems. This openness enables the partner ecosystem we're deliberately cultivating, where we encourage vetted partners to offer compatible subcomponents and upgrades rather than trying to be the sole source for every possible capability our customers might need. We see Blackwing's role not as gatekeepers of a closed ecosystem but as enablers of an open one where the best solutions can emerge from anywhere and integrate seamlessly.

Perhaps most ambitiously, we're actively working to address the pinout standardization gap that plagues PC/104 implementations. Our vision is to create genuine LEGO-like connectivity where electrical interfaces are as standardized as mechanical ones, where a power module from one vendor can truly plug directly into a flight computer from another without custom harnesses or adapter boards, and where customers can mix and match components based on their mission needs with confidence that integration will be straightforward. This requires going beyond existing standards to define power bus voltages, data bus protocols, connector pinouts, and software interfaces that enable genuine interoperability.

The Broader Ecosystem: Who's Driving Standards Forward

While we're passionate advocates for open standards, we're realistic about the fact that no single company, however committed, can define and drive adoption of standards across an entire industry. Meaningful standardization requires broad participation from multiple stakeholders, and we see encouraging signs that the nanosatellite ecosystem is increasingly oriented toward this kind of collaborative standardization.

Companies like Spacedock are addressing critical gaps in orbital infrastructure standards, developing what they describe as the USB standard for space—universal connectors that enable satellites and other space systems to connect, exchange power and data, and support servicing and logistics operations. While their focus on on-orbit interfaces differs from our emphasis on satellite internal architecture, the underlying philosophy aligns perfectly: space infrastructure needs common interfaces that enable different systems to work together rather than requiring everything to come from a single integrated provider.

The open-source hardware community has been instrumental in driving practical standardization through projects that provide working reference implementations rather than just abstract specifications. LibreCube's comprehensive designs for CubeSat subsystems, including their SpaceCAN bus architecture, demonstrate how open-source projects can establish de facto standards by providing high-quality implementations that others adopt and build upon. OreSat's complete, flight-proven satellite designs similarly create templates that subsequent missions can use, modify, and improve while maintaining core compatibility.

Academic institutions play a crucial role in standards development and adoption, particularly through consortia such as the Nanosatellite and CubeSat Workshop community, which brings together university teams, industry partners, and government stakeholders to share experiences and develop common approaches. Universities have a particular incentive to support open standards since they enable student teams to focus on mission-unique aspects rather than reinventing basic spacecraft functions, and the educational mission of universities naturally aligns with openly sharing knowledge and designs.

Government agencies and prime contractors are increasingly recognizing that open standards benefit their programs by enabling competition, reducing vendor lock-in, and accelerating development timelines. When government programs specify open standards for interfaces and data formats, they create market incentives for commercial vendors to support those standards, driving ecosystem-wide adoption far more effectively than bottom-up efforts from small companies alone could achieve.

The commercial satellite industry itself, particularly mega-constellation operators who need to produce satellites at unprecedented scale and cost efficiency, has a powerful economic motivation to drive standardization. These operators need supply chains that can deliver hundreds or thousands of compatible components from multiple vendors, and that kind of supply chain only exists when interfaces are standardized. As these large commercial players mature their architectures and publish interface standards, the broader small satellite community benefits from being able to build to those same standards.

Software and Firmware: The Overlooked Standardization Frontier

While much of the standards discussion in small satellites focuses on hardware interfaces and communication protocols, software and firmware standardization may ultimately prove even more critical for enabling the modular, rapidly evolving satellite systems that the industry needs. Software touches every aspect of spacecraft operations, from boot-time initialization and health monitoring to payload control and ground communication, and the lack of software standards creates integration challenges that are often more severe than hardware incompatibilities.

The open-source software movement has demonstrated in countless domains how collaborative development around shared codebases can produce robust, feature-rich systems that individual organizations couldn't develop in isolation. In the nanosatellite world, flight software frameworks like NASA's Core Flight System provide proven architectures for building satellite control software, with extensive flight heritage and active development communities. However, adoption of these frameworks in commercial small satellites remains limited, often because companies worry that using open-source software means forfeiting competitive advantages or that they'll be responsible for supporting software developed by others.

At Blackwing, we're taking a different view. We see open-source flight software and well-defined software interfaces as enablers that let us focus our limited engineering resources on the aspects of our platform that truly differentiate us, rather than spending time reimplementing functionality that already exists. Our software-defined spacecraft concept, where functions can be updated over the air and missions can be re-tasked through software changes, becomes dramatically more powerful when the software architecture is open and well-documented, allowing customers and partners to develop their own applications and modifications.

The real power comes from standardizing not just the software itself but the interfaces between software components. If there's a standard API for how flight software communicates with a radio, then radio manufacturers can provide driver software that plugs into any flight software stack supporting that API, and satellite operators can swap radio hardware without rewriting large portions of their control software. If payload interfaces are standardized, then payload developers can write control software once and have it work across different satellite platforms. This kind of interface standardization creates the "LEGO-like" modularity we're pursuing, where software components are as interchangeable as we want hardware components to become.

Implementation Challenges and Practical Realities

Advocating for open standards is easier than successfully implementing them, and it's essential to be realistic about the challenges involved. Standards development is time-consuming and requires building consensus among stakeholders with different priorities and often competing interests. Companies worry that supporting open standards will reduce their competitive differentiation or make it easier for competitors to copy their innovations. Technical decisions that seem straightforward can become contentious when different organizations have made different architectural choices and don't want to abandon their existing investments.

There's also a legitimate tension between standardization and innovation. Standards necessarily lag behind the cutting edge because they codify practices that are already well-understood and proven, while innovation often requires trying approaches that deliberately break from established patterns. If standards become too rigid or comprehensive, they can stifle experimentation and lock the industry into suboptimal approaches. Finding the right balance—standardizing what truly needs to be common while preserving flexibility for innovation—requires careful judgment and willingness to evolve standards as the technology and industry mature.

At Blackwing, we're navigating these challenges by being strategic about what we standardize and how. We're focusing on interface standards that enable interoperability without dictating implementation details behind those interfaces. We want to standardize what comes out of a power regulator and what signals it responds to, but not necessarily how that regulator is designed internally. We want to standardize how software components communicate but not mandate specific algorithms or features. This approach tries to get the benefits of standardization while preserving room for proprietary innovation and continuous improvement.

We're also recognizing that standards adoption often happens gradually rather than through immediate wholesale transformation. We design our systems to support both legacy interfaces and new standardized ones, providing bridges that let customers transition incrementally. We participate actively in standards development organizations and industry working groups, sharing our perspectives and learning from others rather than trying to impose Blackwing-specific approaches unilaterally. And we're patient, understanding that building genuine consensus around standards takes time and that forcing adoption before the community is ready usually backfires.

The Vision: A Truly Modular Space Ecosystem

Looking forward, the vision that drives our commitment to open standards is a space industry that works more like the personal computer industry than like traditional aerospace. In the PC world, you can build a high-performance system by selecting a processor from Intel or AMD, a graphics card from NVIDIA or AMD, memory from any of dozens of manufacturers, storage from various vendors, and a motherboard that brings it all together, with confidence that these components from different companies will work together seamlessly because they all adhere to open standards for physical interfaces, electrical signaling, and software drivers.

Imagine a similar ecosystem for nanosatellites. A mission developer could select a flight computer from one vendor, a radio from another, power system from a third, and attitude control hardware from a fourth, with these components coming from companies in different countries, all integrating cleanly because they follow common standards for mechanical mounting, electrical interfaces, and software APIs. Payload developers could build cameras, sensors, or scientific instruments knowing that if they follow the standard payload interface, their products will work on any standards-compliant satellite platform. Ground station operators could build infrastructure that communicates with any satellite following standard protocols rather than requiring custom configurations for each customer.

This vision extends beyond just hardware modularity to operational and data standards. Digital twin technology, which we see as crucial for simulation, testing, and operations, becomes far more powerful when there are standard formats for representing spacecraft models and state information that work across different simulation environments and analysis tools. Our "everything-as-a-Service" approach to FCC licensing, ground stations, mission control, and data services works better when these services can interact with satellites through standardized interfaces rather than requiring custom integration for each platform.

The sustainable design and responsible orbital stewardship that we emphasize in our core concepts also benefits from standardization. If satellites follow common interfaces for refueling, if deorbit systems use standard attachment points, if salvaged components have known specifications, then the servicing and recycling infrastructure that sustainable space operations require becomes economically viable in ways that would be impossible if every satellite is a unique snowflake requiring custom tooling and procedures.

At Blackwing Space, we're building our platforms from day one with this vision of modular ecosystem enablement in mind. Every interface we design, every API we publish, every partnership we pursue is evaluated against the question of whether it moves us toward or away from genuine interoperability and openness. We're betting that customers increasingly value the flexibility and future-proofing that open standards provide over the illusory security of proprietary lock-in. We believe the satellite industry will grow faster and serve more diverse needs when the barriers to entry drop through standardization, when innovation can come from specialized component providers rather than requiring vertical integration, and when the entire community can build on shared foundations rather than everyone starting from scratch.

The need for open standards in nanosatellite development isn't just about making engineers' lives easier or reducing integration costs, though those benefits alone would justify the effort. It's about fundamentally transforming how quickly we can move from ideas to orbit, how many organizations can participate in space missions, how reliably satellites execute their missions, and, ultimately, how effectively we can use space infrastructure to address challenges and opportunities here on Earth. The companies, institutions, and individuals who recognize this need and work actively to advance open standards aren't just serving their own interests but building the foundation for an industry that can scale to meet the extraordinary potential of the space age we're entering.