Radiation Shielding Strategies and Options in Nanosatellite Design

When you're designing a nanosatellite, particularly one like Blackwing Space's modular platforms that leverage automotive-grade electronics to achieve cost advantages, radiation protection becomes one of your most critical engineering challenges. The space environment presents radiation threats that terrestrial electronics were never designed to withstand, and understanding how to protect your spacecraft's brain and nervous system from this invisible enemy can mean the difference between a successful multi-year mission and a satellite that fails within weeks of reaching orbit. The good news is that radiation shielding technology is advancing rapidly, with innovative materials and strategies emerging from startups and research labs that make it increasingly practical to build radiation-resilient nanosatellites without resorting exclusively to expensive space-grade components.

Understanding the Radiation Challenge in Space

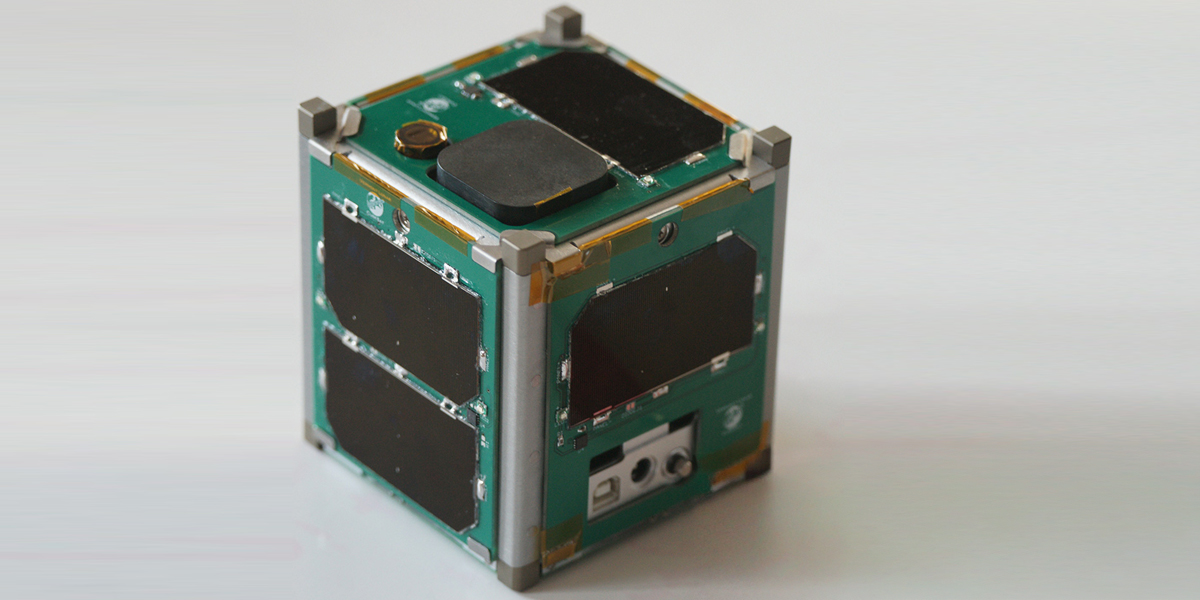

Before we can talk intelligently about shielding strategies, we need to understand what we're actually protecting against. The space radiation environment is fundamentally different from anything electronics experience on Earth's surface, where our atmosphere and magnetic field provide natural shielding that we take completely for granted. In low Earth orbit, which is where most CubeSats and nanosatellites operate, spacecraft face three primary radiation threats that can damage or destroy electronic systems.

The first threat comes from trapped radiation belts, often called the Van Allen belts, which are regions of high-energy protons and electrons captured by Earth's magnetic field. Think of these belts as invisible donuts of concentrated radiation surrounding our planet. When a satellite passes through these regions, its electronics are bombarded by energetic particles that can cause immediate damage or gradual degradation over time. The intensity of this radiation varies with altitude, orbital inclination, and solar activity, but any satellite spending significant time in these regions needs protection.

The second threat is galactic cosmic rays, which are high-energy particles originating from outside our solar system, accelerated by distant supernovae and other cosmic events. These particles are incredibly energetic and can penetrate substantial shielding. While the flux of galactic cosmic rays is relatively low compared to trapped radiation, individual particles can cause significant damage when they strike sensitive electronics. These cosmic rays are essentially impossible to completely shield against with practical amounts of material, so strategies for dealing with them often focus on error detection and correction rather than pure physical blocking.

The third threat comes from solar particle events, which are bursts of radiation emitted by the sun during solar flares and coronal mass ejections. These events are unpredictable and can dramatically increase radiation levels for hours or days. A satellite that's adequately protected under normal conditions might face serious risk during a major solar event, particularly if it's in a higher-altitude orbit with less protection from Earth's magnetic field.

What makes radiation dangerous to electronics isn't just that it exists but how it interacts with the materials in semiconductors. When a high-energy particle strikes a transistor or memory cell, it can deposit enough charge to flip a bit from one to zero or vice versa. This is called a single-event upset, and while it might sound trivial, imagine what happens when a bit flip occurs in a command register controlling your attitude control system or in the memory storing critical navigation data. Even more seriously, radiation can cause permanent damage to semiconductor structures, gradually degrading performance over time through what's called total ionizing dose effects. Automotive-grade electronics, designed for perhaps fifteen years of operation in a car experiencing minimal radiation exposure, might accumulate a lifetime's worth of radiation damage in months or even weeks in certain orbital environments.

The Automotive-Grade Component Challenge and Opportunity

At Blackwing Space, our strategic use of automotive-grade components creates both challenges and opportunities when it comes to radiation protection. Automotive electronics have become remarkably sophisticated and reliable, with modern vehicles containing dozens of processors, sensors, and control systems that must function flawlessly in challenging conditions. These components are designed to handle wide temperature ranges, vibration, electromagnetic interference, and other environmental stresses. They're manufactured in high volumes with mature quality processes, which means they're cost-effective and readily available compared to specialized space-grade parts that might be produced in quantities of hundreds or thousands rather than millions.

However, automotive components are not designed with space radiation in mind. The semiconductor processes used to manufacture them often make them more vulnerable to radiation effects than older, larger-geometry space-grade parts. Modern automotive chips use tiny transistor features measured in nanometers, which makes them faster and more power-efficient but also more susceptible to single-event effects. A particle strike that might harmlessly pass through a larger transistor can cause significant disruption in these miniaturized structures.

This is where intelligent shielding strategies become essential rather than optional. If we can provide effective radiation protection at the system level, we can leverage the cost, performance, and availability advantages of automotive-grade components while achieving reliability comparable to traditional space-grade solutions. This isn't just theoretical speculation but an approach being validated by multiple commercial satellite operators who are flying automotive and commercial components successfully by combining them with thoughtful radiation mitigation strategies.

Our approach at Blackwing involves multiple layers of defense. We start by selecting automotive-grade components that have characteristics making them more radiation-tolerant, such as those using silicon-on-insulator fabrication processes or those with inherent error correction capabilities. We then provide options for customers who need higher radiation tolerance, offering space-grade alternatives for critical subsystems while keeping the overall platform architecture modular enough to accommodate either choice. But regardless of which component grade a customer selects, physical shielding plays a crucial role in extending operational lifetime and reducing error rates.

Traditional Aluminum Shielding: The Baseline Approach

Aluminum has been the workhorse shielding material in spacecraft design for decades, and for good reason. Aluminum offers a favorable combination of shielding effectiveness, low weight, machinability, and well-understood properties that make it a natural baseline choice. When we talk about aluminum shielding in the context of nanosatellites, we're typically discussing aluminum structures that serve double duty, providing both mechanical support and radiation protection.

The physics of how aluminum shields against radiation is straightforward for lower-energy particles. The material simply absorbs or deflects incoming particles through electromagnetic interactions. A few millimeters of aluminum can effectively stop lower-energy protons and electrons, reducing the radiation dose reaching electronics inside. For a nanosatellite, this might mean designing your satellite structure itself to provide shielding, using aluminum walls thick enough to offer meaningful protection without making the spacecraft prohibitively heavy.

However, aluminum has limitations that become increasingly apparent as radiation energy levels increase. High-energy particles, particularly the galactic cosmic rays we discussed earlier, can penetrate substantial thicknesses of aluminum. Even more problematically, when very high-energy particles strike aluminum atoms, they can create secondary radiation through a process called spallation, where the impact fragments aluminum nuclei into smaller particles that can themselves cause damage. This means that beyond a certain point, adding more aluminum doesn't proportionally increase protection and might even make certain problems worse.

For typical low Earth orbit missions, which is where most CubeSats and nanosatellites operate, aluminum structures providing on the order of two to five millimeters of shielding can meaningfully reduce radiation exposure from trapped belt particles. This isn't enough to create a radiation-free environment inside your satellite, but it can reduce dose rates significantly enough to extend component lifetimes and reduce error rates. The key is being strategic about where you place sensitive electronics within your spacecraft structure, positioning them where they benefit from maximum shielding from surrounding components, batteries, and structural elements.

At Blackwing, our modular platform design allows us to integrate aluminum shielding into the structural framework in ways that provide baseline protection without requiring customers to add significant mass or volume. The satellite's chassis, mounting panels, and structural components can be designed with radiation shielding as one of their design objectives, not just mechanical support. This creates what we might call passive shielding that comes essentially for free, since you need structure anyway.

Advanced Composite Shielding: The Next Generation

While aluminum provides a solid baseline, recent advances in composite shielding materials are opening up new possibilities for achieving better protection with less mass. This is where companies like Melagen Labs and Cosmic Shielding Corporation are developing innovative solutions that could significantly improve radiation protection for small satellites. These advanced materials take different approaches to the shielding challenge, but they share a common goal of providing better protection per unit mass than traditional aluminum.

Hydrogen-rich composite materials represent one of the most promising approaches to radiation shielding. The physics behind this is elegant and counterintuitive. When high-energy particles strike hydrogen atoms, which have the smallest atomic nucleus possible consisting of just a single proton, the interactions tend to scatter the particles rather than fragment them into secondary radiation. Materials incorporating high concentrations of hydrogen, such as certain polymers and specialized composites, can therefore provide effective shielding against high-energy particles while actually generating less secondary radiation than aluminum. The challenge has been developing materials that incorporate sufficient hydrogen while maintaining the structural properties, outgassing characteristics, and thermal stability required for spacecraft applications.

Melagen Labs is working on composite materials specifically engineered for space radiation protection, developing formulations that combine hydrogen-rich polymers with other elements chosen to optimize the shielding response across different energy ranges. Their approach recognizes that no single material shields optimally against all radiation types, so they're creating layered composites where different layers address different parts of the radiation spectrum. An outer layer might be optimized for high-energy galactic cosmic rays, while inner layers focus on lower-energy trapped radiation that penetrated the outer shield.

Cosmic Shielding Corporation is taking a somewhat different approach, developing materials that can be integrated into existing spacecraft structures and components. Rather than requiring complete redesign of a satellite around new materials, their solutions can potentially be added to conventional spacecraft designs as supplementary shielding. This modular approach aligns well with Blackwing's philosophy of creating flexible platforms where customers can select the level of radiation protection appropriate for their specific mission.

The practical advantage of these advanced composites becomes clear when you run the mass calculations. If you can achieve equivalent radiation protection with half the mass of an aluminum solution, that mass savings can be applied to additional payload capacity, more propellant for extended missions, or simply reducing overall launch costs. For nanosatellites where every gram matters and where you're often fighting to fit capabilities within a very constrained mass budget, this can be transformative.

However, we need to be realistic about the maturity and availability of these advanced materials. Unlike aluminum, which has decades of flight heritage and well-characterized properties, newer composite shielding materials are still building their track records. This doesn't mean they're unproven or unreliable, but it does mean that incorporating them into spacecraft designs requires careful testing, characterization, and validation. At Blackwing, as we plan our integration of these materials, we're taking a measured approach that balances innovation with the need for demonstrated reliability.

Integrated Shielding Strategies: System-Level Thinking

The most effective radiation protection strategies don't rely on any single material or approach but instead integrate multiple techniques into a comprehensive system-level solution. At Blackwing Space, this is how we're thinking about radiation resilience as we develop our nanosatellite platforms. Rather than asking whether to use aluminum or advanced composites or space-grade components, we're asking how to optimally combine different approaches to achieve the radiation tolerance our customers need while maintaining the cost and performance advantages that make our platforms attractive.

Our planned approach starts with strategic placement of components within the spacecraft structure. Even without adding dedicated shielding materials, thoughtful layout can provide significant protection by positioning sensitive electronics where they benefit from shielding provided by other components. Batteries, for example, provide excellent radiation shielding due to their density and can be strategically located to shield critical processors and memory. Propellant tanks, structural elements, and even payload components can all contribute to the overall shielding environment. By modeling the radiation environment and dose rates throughout our spacecraft structure, we can identify locations that naturally receive more protection and place our most radiation-sensitive components there.

The next layer involves our modular approach to component selection. For customers whose missions have modest radiation requirements, perhaps because they're flying in lower-altitude orbits for relatively short durations, automotive-grade components with baseline aluminum structural shielding might provide perfectly adequate protection. For more demanding missions, perhaps those in higher-radiation orbits or requiring multi-year lifetimes, we can substitute space-grade components in critical subsystems while maintaining the same overall platform architecture. This modularity means customers aren't forced into an all-or-nothing choice between cheap-but-risky and expensive-but-bulletproof, but can instead optimize their radiation protection strategy to their specific mission profile.

Advanced composite shielding from partners like Melagen Labs and Cosmic Shielding Corporation fits into our strategy as targeted protection for particularly sensitive subsystems or for missions with elevated radiation requirements. Rather than shielding the entire spacecraft with advanced composites, which might be cost-prohibitive, we can use these materials selectively where they provide the most value. Imagine wrapping your spacecraft's main computer board in a composite shield that provides the equivalent protection of much thicker aluminum but at a fraction of the mass penalty. This targeted approach maximizes the benefit while controlling costs and maintaining design flexibility.

We're also planning to potentially incorporate radiation monitoring into select platforms, providing customers with real-time data about the radiation environment their spacecraft is experiencing. This serves multiple purposes. First, it allows operators to understand when their satellite is passing through particularly high-radiation regions and potentially adjust operations accordingly, perhaps avoiding critical maneuvers during peak radiation exposure. Second, it provides valuable data for understanding how radiation protection strategies are performing in actual flight conditions, creating a feedback loop that informs future design improvements. Third, it enables adaptive strategies where the spacecraft might automatically enter protective modes during high-radiation events, shutting down non-essential systems or increasing error checking in critical ones.

Practical Implementation Considerations

As we move from theory to actual spacecraft integration, several practical considerations shape how we implement radiation shielding in nanosatellite designs. The first is simply the mass budget reality. Every gram of shielding material is a gram that's not available for payload, propulsion, or other mission-critical functions. This forces careful optimization where we're constantly asking whether additional shielding actually improves overall mission success probability or whether that mass would be better used elsewhere.

Thermal management interacts closely with radiation shielding in ways that aren't always obvious. Materials that provide good radiation protection might have thermal properties that create new challenges. For example, some composite materials have lower thermal conductivity than aluminum, which means that while they might shield electronics from radiation, they might also make it harder to remove waste heat. Our thermal design needs to account for how shielding materials affect heat flow throughout the spacecraft, ensuring that we don't solve a radiation problem while creating a thermal one.

Manufacturing and integration practicality also matters tremendously. A shielding solution that looks perfect in analysis but requires complex fabrication or creates difficult integration challenges might not be the best choice for a modular platform designed for relatively high production volumes. This is one reason why we're interested in solutions like Cosmic Shielding's approach that can integrate with conventional spacecraft structures rather than requiring complete redesigns. The easier it is to incorporate advanced shielding into our standard platform, the more readily we can offer it as an option to customers.

Cost is an ever-present consideration, particularly for commercial missions and university customers operating on limited budgets. Advanced composite materials are typically more expensive than aluminum on a per-kilogram basis, though the total cost might be comparable if the mass savings from composites allows using a smaller launch vehicle slot or accommodating additional payload. We need to be transparent with customers about these trade-offs, helping them understand what different shielding strategies cost and what performance they buy.

Finally, there's the question of qualification and acceptance. Some customers, particularly government agencies and established aerospace companies, have specific requirements for materials that can be used in spacecraft, often based on extensive testing and flight heritage. Introducing new shielding materials into designs that will face these requirements means planning for the testing and qualification activities needed to demonstrate that materials meet applicable standards. This is a process we're engaging with as we evaluate partnerships with companies developing advanced shielding materials, ensuring that as these materials mature and build flight heritage, they're positioned to meet customer requirements.

The Path Forward: Building Radiation-Resilient Platforms

The radiation protection strategy we're developing at Blackwing Space reflects our broader philosophy of building capable, flexible nanosatellite platforms that serve diverse customer needs without forcing everyone into the same solution. By combining traditional aluminum shielding in our structural design, offering modular options for space-grade component upgrades, and planning integration pathways for advanced composite materials from innovative suppliers, we're creating a framework where radiation protection can be tailored to specific mission requirements rather than being a one-size-fits-all proposition.

This approach acknowledges that radiation requirements vary dramatically across different mission profiles. A CubeSat deployed from the International Space Station for a six-month technology demonstration has radically different radiation exposure than a nanosatellite in a higher-altitude orbit planning for a three-year operational lifetime. Rather than overdesigning the first mission with protection it doesn't need or underprotecting the second mission to save costs, our modular approach allows right-sizing radiation protection to each situation.

As advanced shielding materials continue maturing and building flight heritage, we anticipate being able to offer increasingly sophisticated protection options without proportional cost or mass increases. The startups developing these materials are addressing real limitations in traditional approaches, and as their solutions transition from research labs to operational spacecraft, they'll open up new possibilities for what nanosatellites can accomplish in challenging radiation environments.

The future of nanosatellite radiation protection isn't about choosing between automotive-grade and space-grade components, or between aluminum and advanced composites, but about intelligently combining these options in ways that optimize the entire system. At Blackwing, that's precisely what we're building toward: platforms where radiation resilience is designed in from the beginning, where customers have genuine choices in how they balance cost against protection, and where we can leverage the best innovations from across the aerospace and materials science communities to push the boundaries of what small satellites can reliably achieve.