ITAR and EAR for Satellite Builders

If you're entering the satellite industry, whether you're building your first CubeSat or planning to purchase spacecraft components, you'll quickly encounter two regulatory frameworks that will shape nearly every business decision you make: the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) and the Export Administration Regulations (EAR). These regulations aren't just bureaucratic hurdles to clear—they fundamentally determine who you can work with, where you can source components, which customers you can serve, and how you can structure your business operations.

Understanding ITAR and EAR: The Basics

Let's start with the fundamental question: what exactly are ITAR and EAR, and why do they matter so much to satellite builders?

The International Traffic in Arms Regulations, commonly known as ITAR, is a set of United States government regulations that controls the export and import of defense-related articles, services, and technical data. ITAR is administered by the Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC), which operates under the U.S. Department of State. When we say something is "ITAR-controlled," we mean it's classified as a defense article that requires government approval before it can be shared with foreign nationals or exported outside the United States.

The Export Administration Regulations, or EAR, are a different but related framework administered by the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) within the U.S. Department of Commerce. EAR controls the export of commercial and dual-use items—products that have both civilian and military applications. While EAR is generally less restrictive than ITAR, it still imposes significant requirements on what can be exported, to whom, and under what circumstances.

Think of it this way: ITAR is designed specifically for military and defense items, while EAR covers a much broader range of commercial products that might have strategic value. The challenge for satellite builders is that spacecraft and related technologies have historically straddled this line, sometimes falling under the stricter ITAR controls and sometimes under EAR, depending on their specific characteristics and intended use.

The key distinction you need to understand is that ITAR operates on a "see-no-touch" principle for non-U.S. persons. If a component or technical data is ITAR-controlled, you generally cannot share it with, show it to, or discuss technical details about it with anyone who isn't a U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident without prior government approval. This includes your own employees if they're foreign nationals, potential customers from other countries, and even engineering contractors working remotely from abroad.

EAR, by contrast, uses a more nuanced approach based on destination countries, end-users, and end-uses. Many items under EAR can be exported to friendly nations without licenses, though certain sensitive technologies, destinations, or parties still require approval. The regulations use a tiered system where some countries face fewer restrictions than others, and certain technologies are more tightly controlled regardless of destination.

The Historical Journey: From Cold War Controls to Commercial Space

To understand why these regulations exist in their current form, we need to travel back to the Cold War era and trace how space technology became entangled with national security concerns.

The foundation for modern export controls was laid in 1949 with the Export Control Act, which gave the U.S. government authority to restrict exports for national security and foreign policy reasons. ITAR itself emerged from the Arms Export Control Act of 1976, which consolidated various defense export regulations into a more comprehensive framework. The underlying principle was straightforward: advanced military technologies should not fall into the hands of adversaries who might use them against American interests.

For decades, this system operated without causing major friction in the commercial space industry, primarily because there wasn't much of a commercial space industry to speak of. Space was the domain of governments, and satellites were largely military or government-sponsored assets. The few commercial satellites that existed were typically built by large defense contractors already familiar with navigating strict export controls.

The watershed moment came in 1999, when Congress passed legislation that moved satellites and related technologies from the more permissive Commerce Control List (under EAR) to the stricter United States Munitions List (under ITAR). This change was driven by concerns about technology transfer to China following investigations into alleged espionage and unauthorized sharing of sensitive rocket and satellite technology. In one swift legislative action, virtually all satellites—regardless of their civilian applications—became defense articles subject to ITAR's stringent controls.

This reclassification had profound consequences that rippled through the industry for more than a decade. American satellite manufacturers found themselves unable to compete effectively in global markets because they couldn't share technical specifications with foreign customers without lengthy government approvals. International collaborations became nightmarishly complex, requiring layers of technical assistance agreements and export licenses. Universities struggled to recruit talented foreign graduate students into aerospace programs because they couldn't legally work on satellite projects. The American space industry, which had dominated global markets, watched its market share erode as international competitors faced no such restrictions.

The turning point came with the 2013 National Defense Authorization Act, which directed the President to review satellite export controls. After years of industry advocacy and government analysis, significant reforms were implemented in 2014 and subsequent years. These reforms moved many commercial communications satellites and their components back to EAR jurisdiction, recognizing that not all space technology required the strictest possible controls. However, the reforms were carefully calibrated—many sensitive technologies remained under ITAR, and even items moved to EAR often still required licenses for export to many countries.

The Satellite Industry Under Export Controls: Practical Realities

Now let's explore how these regulations actually affect the day-to-day operations of satellite builders, particularly those working on smaller spacecraft like CubeSats.

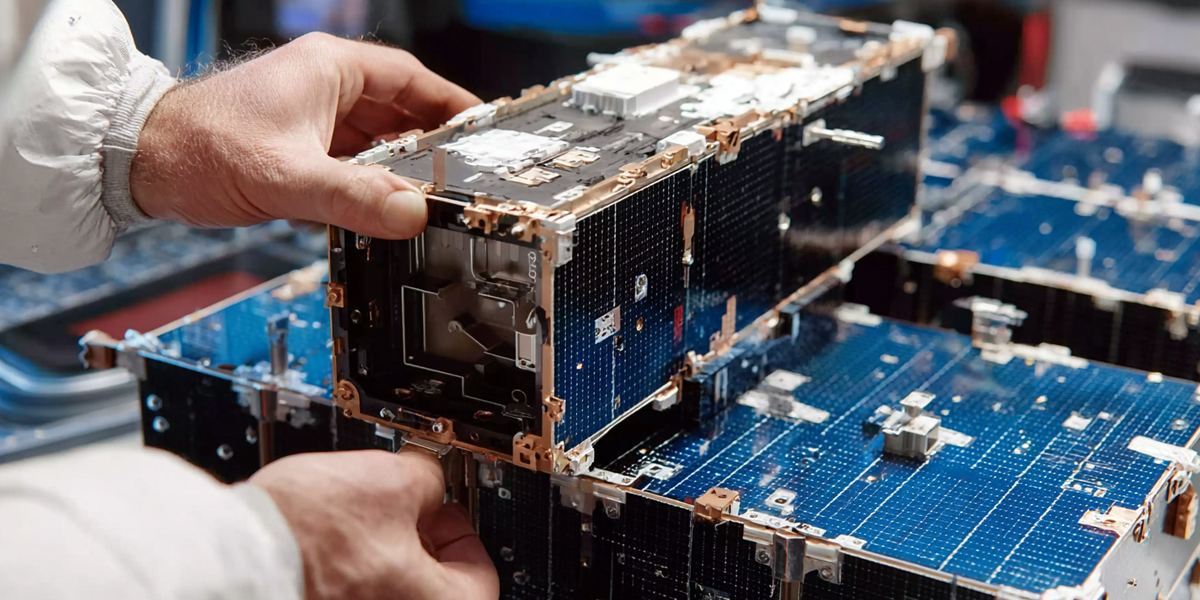

The first challenge you'll face is determining which regulatory framework applies to your specific spacecraft and components. This isn't always straightforward. A satellite might contain a mix of ITAR-controlled and EAR-controlled components, or it might use entirely commercial off-the-shelf parts that aren't subject to either regime. The jurisdiction depends on factors including the satellite's capabilities, its intended mission, specific technical specifications, and how various components are classified.

For CubeSat builders, there's both good news and complexity here. Many CubeSats use relatively standard commercial components—things like consumer-grade processors, solar cells, and batteries—that fall outside strict export controls or qualify for license exceptions under EAR. However, once you start incorporating more sophisticated elements like high-resolution imaging systems, encrypted communications, advanced propulsion, or radiation-hardened electronics designed for space, you're more likely to encounter controlled technologies.

Let's walk through what this means in practice. Imagine you're designing a CubeSat for Earth observation. Your basic bus structure, power systems, and attitude control might use commercial components with minimal export restrictions. But your imaging payload could be a different story. High-resolution imaging capabilities are considered sensitive because they have intelligence applications. If your camera system can achieve certain resolution thresholds, it might be ITAR-controlled or require an EAR license for export. The specific resolution threshold that triggers controls has been a moving target over the years, but it's something you need to verify for your particular design.

This creates interesting strategic decisions for companies like those building modular satellite platforms. If you design your spacecraft bus using entirely domestic, non-controlled components, you maximize your flexibility to work with international customers and partners. You can share technical details freely, collaborate with foreign engineers, and potentially export finished spacecraft without extensive licensing. However, this might mean using components that are more expensive, less capable, or harder to source than readily available international alternatives.

The people challenge is equally significant. Under ITAR, you cannot employ foreign nationals to work on ITAR-controlled projects unless they obtain special authorization. This means if you hire a talented engineer from Canada, the UK, or any other country, they cannot access ITAR technical data or work on ITAR projects until they either become a U.S. citizen, obtain lawful permanent residency, or you secure specific approval for their involvement. This has real implications for hiring, team structure, and how you organize your engineering work.

Some companies address this by creating "clean teams" of only U.S. persons who work on ITAR-controlled aspects, while foreign nationals work on non-controlled subsystems. Others choose to avoid ITAR-controlled technologies entirely, building their spacecraft using only EAR or non-controlled components so they can tap into global talent pools without restriction. There's no universal right answer—it depends on your mission requirements, target markets, and business strategy.

The compliance burden is substantial and ongoing. If you're working with ITAR-controlled technologies, you must register with the DDTC, which involves fees and annual renewals. You need robust internal controls to prevent unauthorized access to technical data, including physical security measures, IT security protocols, and employee training. You must carefully document any exports or transfers, maintain detailed records, and potentially undergo audits. For a small startup or university team, these requirements can represent significant overhead in both money and management attention.

When it comes to selling satellites or components internationally, the licensing process varies dramatically based on what you're selling and to whom. Under the reformed regulations, exports of many commercial satellites to NATO allies and other friendly nations may qualify for license exceptions or expedited processing. However, sales to countries of concern still require detailed license applications that can take months to process, if they're approved at all. You'll need to provide technical specifications, end-user information, and assurances about how the technology will be used.

What CubeSat Developers Need to Know

For those specifically working on CubeSat projects, whether as university researchers, startup founders, or commercial operators, there are several key considerations that deserve special attention.

First, understand that CubeSats exist in a unique regulatory space. Because many CubeSats are built for educational or scientific purposes using relatively standard commercial components, they often avoid the strictest controls. However, the moment you start pushing the performance envelope—developing high-performance imaging, advanced propulsion, sophisticated communications, or other cutting-edge capabilities—you're more likely to trigger export control requirements.

University programs need to be particularly careful about international collaboration and foreign student involvement. Many universities have developed specialized programs to train foreign students on export control compliance and carefully structure projects to allow maximum participation while maintaining compliance. Some create separate tracks where U.S. person students work on controlled technologies while international students focus on non-controlled aspects or theoretical work. Others choose to avoid controlled technologies entirely in student projects.

If you're sourcing components for your CubeSat, you need to understand the export control status of each item you purchase. Reputable suppliers in the space industry typically provide export control classifications for their products, but it's ultimately your responsibility to make correct determinations. Some components might be controlled for export even though they're readily available for purchase within the United States. The mere fact that you can buy something domestically doesn't mean you can freely share information about it with foreign persons or export it internationally.

The rise of commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components in CubeSat design has generally helped reduce export control burdens, as many COTS parts are either not controlled or are more easily exportable under EAR. However, even COTS components can become controlled based on how they're used or modified. If you take a commercial processor and radiation-harden it for space applications using proprietary techniques, you might create technical data that's now controlled even though the original component wasn't.

Launch considerations add another layer of complexity. When you launch a satellite on a foreign launch vehicle or from a foreign launch site, you're technically exporting that satellite. This requires either a license or a license exception, depending on the satellite's specifications and the launch location. Even if your CubeSat is deployed from the International Space Station, which seems like neutral territory, there are export control implications since it involves international partners and potential access by foreign nationals.

Building a Compliance-Forward Business Strategy

For companies entering the satellite market, export control compliance shouldn't be an afterthought—it should be integrated into your business strategy from day one. The decisions you make about technology choices, workforce composition, target markets, and partnership structures all have export control implications that can either limit or expand your opportunities.

One increasingly popular approach is to design "ITAR-free" spacecraft platforms using only components that are either not controlled or fall under EAR with favorable export classifications. This strategy requires careful component selection and sometimes accepting performance trade-offs, but it can dramatically simplify international business, collaboration with foreign partners, and workforce flexibility. Companies pursuing this approach emphasize their ability to work with international customers without the lengthy delays and uncertainties of ITAR licensing.

The alternative is to embrace ITAR or stricter EAR controls as a competitive advantage. Some companies argue that using the most advanced, often ITAR-controlled technologies gives them performance advantages that justify the regulatory burden. They focus primarily on U.S. government customers and domestic commercial clients, or they accept the complexity of international licensing as a cost of doing business with cutting-edge capabilities.

Understanding deemed exports is crucial for any satellite builder. A deemed export occurs when you share controlled technical data with a foreign national, even if that person is physically located in the United States. This means if you hire a talented engineer from another country and they access ITAR technical data at your U.S. facility, that's legally considered an export to their country of nationality and requires appropriate authorization. Many companies have inadvertently violated export controls through deemed exports because they didn't realize that simply showing foreign employees certain information constituted an export.

Record-keeping and compliance programs are essential, not optional. Even if you determine that your technology isn't currently controlled, you need documentation supporting that determination. If you apply for export licenses, you must maintain detailed records. If you're subject to ITAR, you need a comprehensive compliance program including employee training, access controls, and regular reviews. The government takes violations seriously, and penalties can include substantial fines, loss of export privileges, and even criminal charges in egregious cases.

Looking Forward: The Evolving Regulatory Landscape

Export controls for space technologies continue to evolve as the industry transforms and geopolitical considerations shift. The regulatory reforms of recent years recognized that the commercial space industry had matured and that blanket controls on all satellite technologies were counterproductive. However, emerging technologies like on-orbit servicing, satellite-to-satellite data relay, advanced propulsion systems, and spacecraft with significant maneuverability are creating new regulatory questions.

There's ongoing tension between enabling American companies to compete globally and protecting national security interests. As more countries develop sophisticated space capabilities and new applications emerge—from mega-constellations providing global internet to commercial space stations—regulators are continuously reassessing where to draw the lines between controlled and non-controlled technologies.

For satellite builders, the key takeaway is that export control compliance requires ongoing attention, not one-time checkbox completion. Regulations change, your technology evolves, your workforce shifts, and new business opportunities emerge—all requiring fresh analysis of export control implications. Building relationships with regulatory agencies, joining industry associations that track regulatory developments, and investing in compliance expertise pays dividends over time.

The good news is that the regulatory system, while complex, is navigable with proper attention and resources. Thousands of companies successfully build, sell, and operate satellites while maintaining export control compliance. By understanding these regulations from the outset, building compliance into your operations, and making informed strategic choices about technology and markets, you can position your satellite venture for success in both domestic and international markets. The companies that thrive aren't necessarily those that avoid export controls entirely, but rather those that understand the rules, make deliberate choices aligned with their business strategy, and maintain robust compliance as they grow.