CircuitPython for Satellites: A Complete Programming Guide for PyCubed

Learn how to program spacecraft using CircuitPython: from Python basics to satellite-specific applications

CircuitPython has revolutionized how we program small satellites. What once required deep embedded systems expertise and C programming skills can now be accomplished by anyone comfortable with Python. But making the transition from desktop Python (or no programming background at all) to writing flight software for a satellite requires understanding some key concepts.

This comprehensive guide will take you from CircuitPython basics to satellite-specific programming, with practical examples, essential resources, and real-world patterns used in PyCubed-based missions.

What is CircuitPython?

CircuitPython is a version of Python designed specifically for microcontrollers. Developed by Adafruit Industries and based on MicroPython, it prioritizes ease of use, rapid development, and hardware accessibility. Unlike traditional embedded development that requires compiling code, flashing firmware, and complex debugging tools, CircuitPython runs directly on the microcontroller and can be edited like any Python script.

For satellite applications, CircuitPython offers compelling advantages: rapid prototyping, extensive library support, easy hardware interfacing, and a gentle learning curve. PyCubed leverages these strengths to make satellite software development accessible to university teams and startups without deep embedded expertise.

CircuitPython vs. Standard Python: What's Different?

If you already know Python, you have a significant head start. CircuitPython maintains Python 3 syntax and supports most common language features. However, there are important differences driven by microcontroller constraints:

Memory Limitations: Desktop Python has gigabytes of RAM available. CircuitPython on microcontrollers (including PyCubed's ATSAMD51) typically has 256KB of RAM. This means you must be conscious of memory usage-large lists, string concatenation, and creating many objects can exhaust available memory. Techniques that are fine on your laptop can crash a satellite.

No Operating System: Standard Python runs on an operating system that handles multitasking, file systems, and resource management. CircuitPython runs "bare metal" on the microcontroller. You don't have multiple processes, threading is limited, and you control hardware directly. This is actually simpler in some ways - no worrying about process isolation or system calls - but requires different thinking about program structure.

Limited Standard Library: Not all Python standard library modules are available in CircuitPython. Modules that require OS features (subprocess, multiprocessing) don't exist. Others are implemented with reduced functionality. You need to check CircuitPython documentation to see what's available.

Hardware Access Built-In: Standard Python requires third-party libraries for hardware access (GPIO, I2C, SPI). CircuitPython has these capabilities built into core modules. This is one of CircuitPython's major advantages - interfacing with sensors, radios, and other hardware is straightforward.

No pip Install: You can't pip install packages on CircuitPython. Instead, libraries are distributed as .py or .mpy files that you copy to the device. The CircuitPython Bundle provides pre-compiled libraries for common hardware and protocols.

Single-Threaded Event Loop: While desktop Python has threading and asyncio for concurrency, CircuitPython programs typically use a single main loop that polls sensors, processes data, and controls hardware. Newer CircuitPython versions support asyncio, but most satellite code uses simpler polling approaches.

Timing Constraints: Microcontrollers run much slower than desktop CPUs. The ATSAMD51 in PyCubed runs at 120MHz - fast for a microcontroller but slow compared to a laptop. Code that runs in milliseconds on your computer might take seconds on hardware. You must think about execution time and optimize accordingly.

Required Background: What You Need to Know

The good news: you don't need to be an expert programmer to write satellite software with CircuitPython. The bad news: you need to learn some new concepts beyond basic Python.

Essential Python Fundamentals:

- Variables, data types (integers, floats, strings, bytes)

- Control flow (if/elif/else, while loops, for loops)

- Functions and parameters

- Lists, tuples, and dictionaries

- Modules and imports

- Basic file I/O

- Exception handling (try/except)

- Classes and objects (helpful but not immediately essential)

If you're new to Python entirely, work through a beginner Python tutorial first. The official Python tutorial, Automate the Boring Stuff with Python, or Python Crash Course are all excellent starting points. Plan to spend 2-4 weeks getting comfortable with these fundamentals.

Embedded Systems Concepts:

Even though CircuitPython abstracts many low-level details, understanding basic embedded concepts helps enormously:

- GPIO (General Purpose Input/Output): How microcontrollers read digital signals (high/low, on/off) and control external devices

- I2C (Inter-Integrated Circuit): A communication protocol used by many sensors and peripherals. You don't need to understand the bit-level protocol, but know that I2C devices have addresses and registers you read/write

- SPI (Serial Peripheral Interface): Another communication protocol, typically faster than I2C, used for displays, SD cards, and high-speed sensors

- UART/Serial: Simple serial communication, often used for GPS modules, radio links, and debugging

- Analog vs. Digital: Understanding that some sensors output analog voltages (0-3.3V) that need conversion to numbers, while others provide digital data

- Pull-up/Pull-down Resistors: Basic electrical concept about ensuring inputs have defined states

- Power Management: How circuits draw current, voltage regulation, and why power budgets matter in space

You don't need an electrical engineering degree, but reading an "Introduction to Embedded Systems" tutorial will help. Adafruit's "Learn Electronics" series and SparkFun's tutorials are excellent free resources.

Satellite-Specific Knowledge:

Writing satellite software requires understanding what a satellite actually does:

- Attitude Determination and Control: How satellites know their orientation (using magnetometers, gyroscopes, sun sensors) and adjust it (using magnetorquers or reaction wheels)

- Communications: How satellites talk to ground stations (radio protocols, modulation, packet structures)

- Power Systems: Solar panel generation, battery management, power budgets

- Thermal Management: Keeping components within operating temperatures in the space environment

- Orbital Mechanics Basics: Understanding orbits, ground station passes, eclipse periods

This knowledge develops over time. Start with introductory CubeSat resources like the CubeSat 101 guide from NASA or university CubeSat textbooks.

Getting Started: Setting Up Your Development Environment

Before writing satellite code, you need a proper development setup. Here's the recommended path:

Step 1: Install CircuitPython on Development Hardware

Don't start by programming your expensive PyCubed flight board. Instead, get a cheap development board for learning:

- Adafruit Metro M4 Express ($25) - Uses same ATSAMD51 as PyCubed

- Adafruit Feather M4 Express ($23) - Smaller form factor, same chip

- Adafruit ItsyBitsy M4 Express ($15) - Tiny but capable

These boards let you learn CircuitPython and develop code safely before deploying to flight hardware. Download the appropriate CircuitPython .UF2 file from circuitpython.org, connect the board via USB, double-tap the reset button to enter bootloader mode, and drag the .UF2 file to the BOOT drive that appears. The board will reboot running CircuitPython.

Step 2: Choose an Editor

You can edit CircuitPython code with any text editor, but specialized tools help:

- Mu Editor: Designed specifically for CircuitPython, with built-in serial console and plotter. Ideal for beginners. Download from codewith.mu

- Visual Studio Code: Professional editor with CircuitPython extension. More powerful but steeper learning curve

- Thonny: Simple Python IDE with CircuitPython support

For satellite development, most teams eventually migrate to VS Code for features like Git integration and advanced search, but Mu is perfect for learning.

Step 3: Install Libraries

Download the CircuitPython Library Bundle matching your CircuitPython version from circuitpython.org/libraries. Extract it and you'll find hundreds of .mpy files. Don't install all of them - they won't fit. Only copy libraries you actually use to the lib/ folder on your CircuitPython device.

Step 4: Serial Console Access

The serial console shows print statements and errors. Mu Editor has this built-in. For other editors, use a serial terminal program like PuTTY (Windows), screen (Mac/Linux), or the Arduino Serial Monitor.

Your First CircuitPython Program

The CircuitPython equivalent of "Hello World" blinks an LED. Create a file called code.py on your CircuitPython device:

import board

import digitalio

import time

led = digitalio.DigitalInOut(board.LED)

led.direction = digitalio.Direction.OUTPUT

while True:

led.value = True

time.sleep(0.5)

led.value = False

time.sleep(0.5)

Save the file. CircuitPython automatically detects the change and restarts, running your code. The built-in LED should blink.

Let's break down what's happening:

- import board: Provides access to the microcontroller's pins

- import digitalio: Library for digital input/output

- import time: Time functions including sleep

- digitalio.DigitalInOut(board.LED): Creates an object controlling the LED pin

- led.direction = digitalio.Direction.OUTPUT: Configures the pin as an output

- while True: Infinite loop (normal for embedded programs)

- led.value = True/False: Turn LED on/off

- time.sleep(0.5): Wait 0.5 seconds

This pattern- initialize hardware, then enter an infinite loop updating hardware- is fundamental to embedded programming.

Reading Sensors: I2C Communication

Most satellite sensors use I2C. Here's how to read a BME280 environmental sensor (temperature, humidity, pressure):

import board

import adafruit_bme280

i2c = board.I2C() # Uses board's default I2C pins

bme280 = adafruit_bme280.Adafruit_BME280_I2C(i2c)

while True:

print(f"Temperature: {bme280.temperature:.1f} C")

print(f"Humidity: {bme280.humidity:.1f} %")

print(f"Pressure: {bme280.pressure:.1f} hPa")

time.sleep(2)

Note how simple this is. The adafruit_bme280 library handles all I2C protocol details. You just read properties. This is CircuitPython's superpower - hardware abstraction that makes sensor interfacing trivial.

For PyCubed development, you'll use similar patterns with IMU sensors (accelerometers, gyroscopes, magnetometers), GPS modules, and radio transceivers.

Satellite-Specific Programming Patterns

Real satellite software is more complex than blinking LEDs, but follows similar patterns. Here are common structures you'll encounter in PyCubed missions:

State Machines:

Satellites operate in different modes: initialization, detumbling, nominal operations, safe mode, communications mode. State machines manage these transitions:

STATE_INIT = 0

STATE_DETUMBLE = 1

STATE_NOMINAL = 2

STATE_SAFE = 3

current_state = STATE_INIT

while True:

if current_state == STATE_INIT:

# Initialize hardware

initialize_sensors()

initialize_radio()

current_state = STATE_DETUMBLE

elif current_state == STATE_DETUMBLE:

# Stabilize rotation

if rotation_stable():

current_state = STATE_NOMINAL

elif current_state == STATE_NOMINAL:

# Normal operations

collect_data()

if check_for_commands():

process_commands()

time.sleep(0.1)

This structure keeps code organized and makes mode transitions explicit.

Telemetry Collection:

Satellites constantly gather data about their health and status:

import struct

def collect_telemetry():

tlm = {}

tlm['timestamp'] = time.monotonic()

tlm['battery_voltage'] = read_battery_voltage()

tlm['solar_current'] = read_solar_current()

tlm['temperature'] = read_temperature()

tlm['gyro_x'], tlm['gyro_y'], tlm['gyro_z'] = read_gyro()

return tlm

def pack_telemetry(tlm):

# Pack into bytes for radio transmission

return struct.pack('

tlm['timestamp'],

tlm['battery_voltage'],

tlm['solar_current'],

tlm['temperature'],

tlm['gyro_x'],

tlm['gyro_y'],

tlm['gyro_z']

)

The struct module packs Python values into compact binary formats suitable for radio transmission - crucial when you have limited bandwidth.

Power Management:

Satellites must carefully manage power consumption:

def enter_low_power_mode():

# Disable non-essential systems

payload.power = False

radio.sleep()

# Reduce sensor sampling rate

sensor_interval = 10 # seconds instead of 1

def check_power_budget():

battery_voltage = read_battery_voltage()

if battery_voltage < LOW_POWER_THRESHOLD:

enter_low_power_mode()

elif battery_voltage > NORMAL_POWER_THRESHOLD:

exit_low_power_mode()

This autonomy - making decisions based on current conditions- is essential for satellite survival.

PyCubed-Specific Libraries and Examples

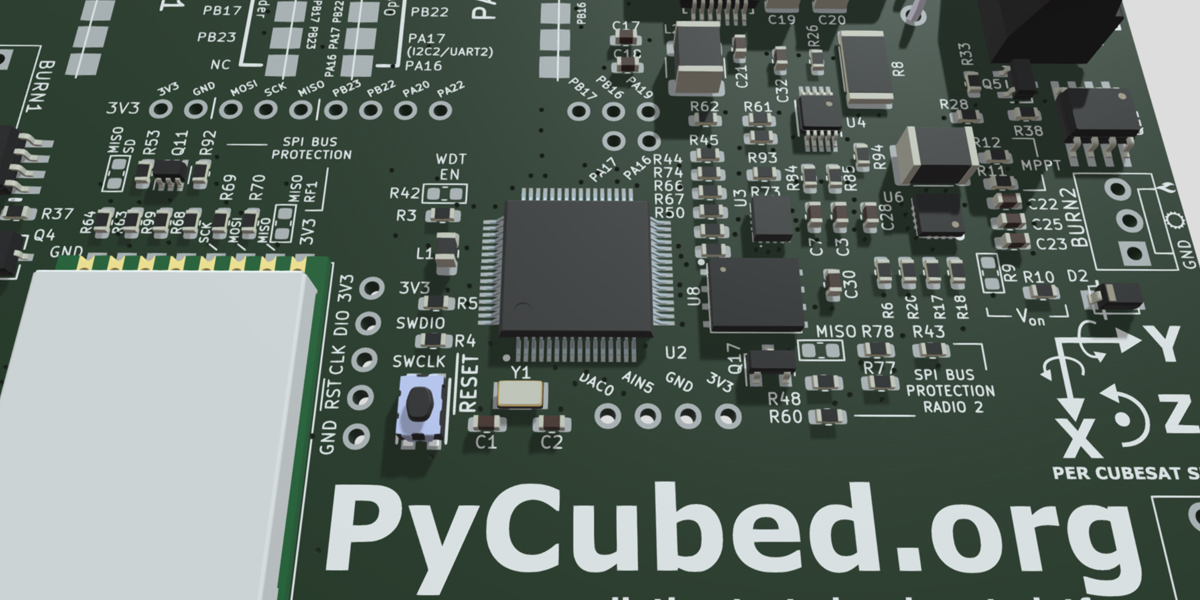

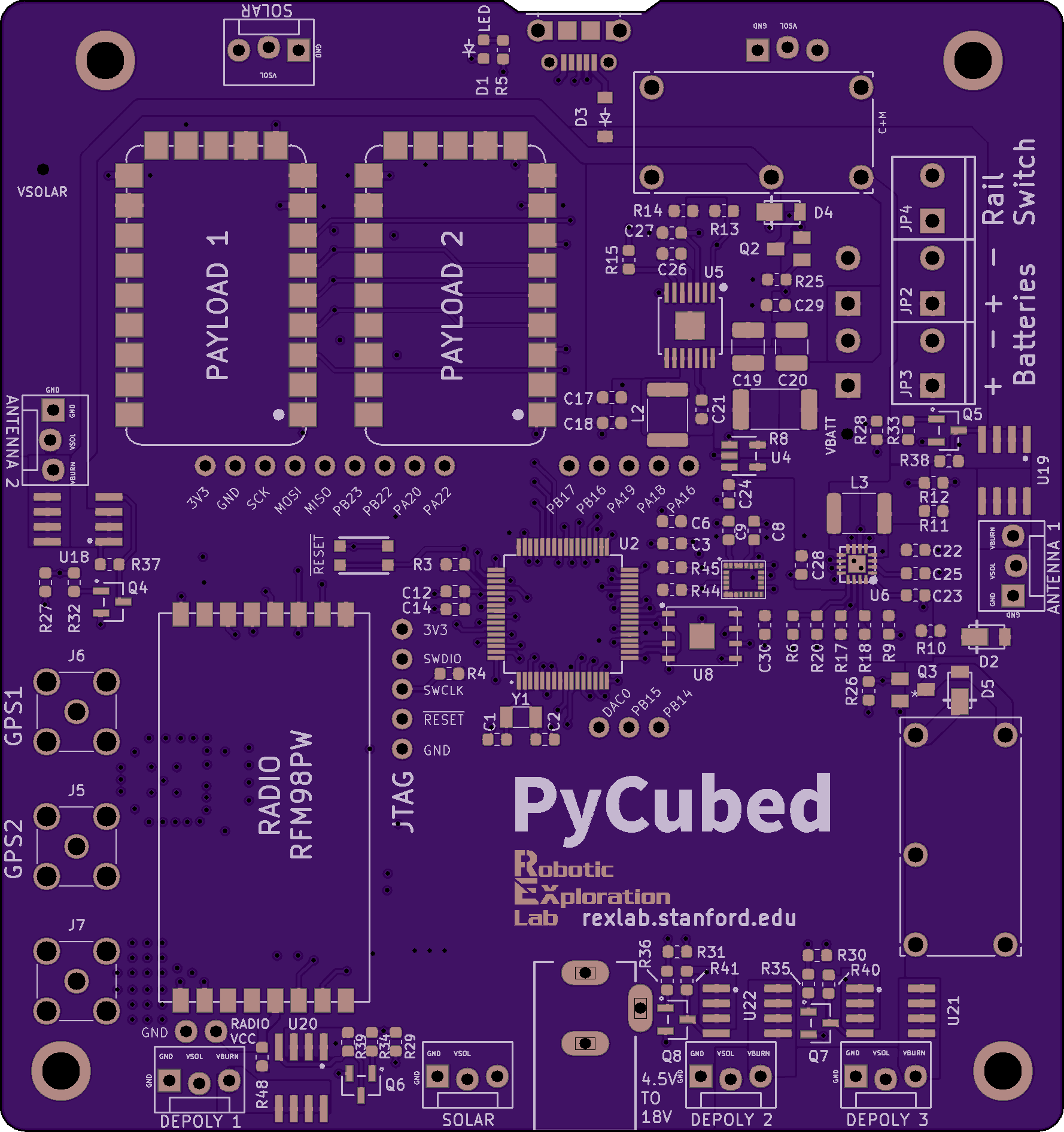

PyCubed comes with custom libraries designed specifically for satellite operations. The PyCubed GitHub repository (github.com/pycubed-mini/flight_software) contains flight-ready examples.

Key PyCubed Libraries:

- pycubed.py: Main library providing hardware abstraction for PyCubed board

- adcs.py: Attitude Determination and Control System functions

- radio.py: Radio communication wrappers

- power.py: Power monitoring and management

- gps.py: GPS interfacing and parsing

Example using PyCubed library:

from pycubed import cubesat

# Hardware initialization handled by library

cubesat.RGB = (0, 255, 0) # Green status LED

cubesat.f_softboot = 0 # Clear boot counter

# Read IMU

accel_data = cubesat.acceleration

gyro_data = cubesat.gyro

mag_data = cubesat.magnetic

# Power monitoring

battery_voltage = cubesat.battery_voltage

battery_current = cubesat.system_current

# Radio communication

cubesat.radio1.send("Hello from orbit!")

The cubesat object encapsulates all hardware interfaces, making code cleaner and more maintainable.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Based on experience from university CubeSat teams and commercial developers, here are mistakes to avoid:

Memory Leaks:

Creating objects in loops without freeing them exhausts memory:

# BAD - creates new list every iteration

while True:

data = [read_sensor() for _ in range(100)]

process(data)

# GOOD - reuse same list

data = [0] * 100

while True:

for i in range(100):

data[i] = read_sensor()

process(data)

Pre-allocate buffers and reuse them rather than creating new objects.

Blocking Operations:

Long time.sleep() calls or blocking I/O prevent the satellite from responding to urgent conditions:

# BAD - satellite unresponsive for 60 seconds

time.sleep(60)

# GOOD - check important conditions while waiting

start_time = time.monotonic()

while time.monotonic() - start_time < 60:

check_battery()

check_for_commands()

time.sleep(1)

Break long delays into short intervals with critical checks in between.

Ignoring Error Handling:

Sensors fail, communications dropout, and unexpected conditions occur. Your code must handle errors gracefully:

try:

temperature = sensor.temperature

except OSError:

# Sensor not responding, use last known value or default

temperature = last_temperature

log_error("Temperature sensor failure")

Always wrap hardware access in try/except blocks.

Not Testing Edge Cases:

Test what happens when sensors return unexpected values, when memory is nearly full, when power is low, when radio communication fails. Satellite software must be robust because you can't physically access the hardware once it launches.

Essential Learning Resources

Here's where to deepen your CircuitPython and satellite programming knowledge:

Official CircuitPython Resources:

- CircuitPython Documentation: docs.circuitpython.org - Comprehensive reference

- Adafruit Learn Guides: learn.adafruit.com/category/circuitpython - Hundreds of hardware tutorials

- CircuitPython Weekly Newsletter: adafruitdaily.com/category/circuitpython - Latest updates and projects

- Discord Community: adafru.it/discord - Active help channel

PyCubed Specific:

- PyCubed GitHub: github.com/pycubed-mini - Hardware designs and flight software

- PyCubed Documentation: pycubed.org - Platform overview and guides

- Stanford SSI Wiki: wiki.stanfordssi.org - Original development team's documentation

Python Learning:

- Official Python Tutorial: docs.python.org/3/tutorial

- Automate the Boring Stuff: automatetheboringstuff.com - Free online book

- Real Python: realpython.com - Intermediate to advanced tutorials

Embedded Systems:

- SparkFun Tutorials: learn.sparkfun.com - Excellent electronics basics

- Adafruit Learning System: learn.adafruit.com - Hardware interfacing guides

- Embedded Systems Course (edX): Various free university courses

CubeSat Development:

- NASA CubeSat 101: nasa.gov/mission_pages/cubesats/overview

- The CubeSat Program (CalPoly): cubesat.org - Standards and specifications

- AMSAT educational resources: amsat.org - Amateur satellite knowledge base

Recommended Learning Path

If you're starting from scratch, here's a realistic timeline:

Month 1-2: Python Fundamentals

- Complete a Python beginner course or book

- Write simple programs: calculators, file processors, data analyzers

- Practice with lists, dictionaries, functions, and file I/O

- Goal: Comfortable writing 50-100 line Python programs

Month 3: CircuitPython Basics

- Get a development board and blink LEDs

- Work through Adafruit CircuitPython Essentials guide

- Interface with 3-5 different sensors (I2C and SPI)

- Build a simple data logger project

- Goal: Confident reading sensors and controlling hardware

Month 4: Embedded Concepts

- Study I2C, SPI, and UART protocols

- Learn about interrupts and timers (even if CircuitPython abstracts them)

- Practice power budgeting and current measurements

- Build a battery-powered remote sensor station

- Goal: Understanding embedded system constraints

Month 5-6: Satellite Applications

- Study CubeSat basics and mission architectures

- Work through PyCubed example code

- Implement a state machine controlling multiple subsystems

- Practice telemetry collection and radio communication

- Build a desktop satellite simulator using PyCubed hardware

- Goal: End-to-end understanding of satellite software

Advanced Topics Worth Exploring

Once you're comfortable with basics, consider these advanced areas:

Asynchronous Programming: Recent CircuitPython versions support asyncio, enabling cooperative multitasking. This allows more sophisticated concurrent operations without traditional threading complexity.

Kalman Filtering: Essential for attitude determination, combining noisy sensor data into accurate state estimates. Python's numerical libraries make implementation straightforward.

PID Control: Proportional-Integral-Derivative controllers for precise attitude control using magnetorquers or reaction wheels.

Communication Protocols: Implementing robust command/telemetry protocols with error detection, packet sequencing, and retry logic.

Bootloaders and Failsafes: Creating recovery mechanisms that allow satellites to recover from software faults autonomously.

Ground Station Software: Building complementary ground station code for mission planning, command generation, and telemetry analysis.

Real-World Development Workflow

Professional satellite development follows structured processes:

Version Control: Use Git to track code changes. GitHub or GitLab for team collaboration. This is non-negotiable for multi-person teams.

Testing Strategy:

- Unit tests for individual functions

- Hardware-in-loop testing with actual sensors

- Flatsat testing (all components laid out on table)

- Integrated spacecraft testing

- Environmental testing (thermal, vibration)

Documentation: Comment your code extensively. Future you (or your teammates) will appreciate understanding what complex sensor fusion algorithms do. Write operational procedures explaining how to command the satellite.

Code Reviews: Have teammates review changes before merging. Catches bugs and spreads knowledge across the team.

Simulation: Test code in simulation before risking hardware. Tools like the PyCubed simulator let you debug logic without physical boards.

Getting Commercial-Grade PyCubed Hardware

As you progress from learning to mission development, you'll need reliable hardware. While development boards are perfect for education, flight missions require professional-grade components.

Blackwing Space manufactures PyCubed-derived onboard computers specifically designed for commercial nanosatellite missions. These boards maintain CircuitPython compatibility while addressing challenges that affect DIY builds: component obsolescence, supply chain reliability, comprehensive testing, and technical support.

For teams serious about launching, commercial PyCubed hardware provides confidence that your flight computer will perform when it matters - in orbit. The same CircuitPython code you develop on cheap learning boards runs on flight hardware, making the transition seamless.

Conclusion: The Future is Python in Space

CircuitPython has democratized satellite software development. What once required teams of specialized embedded programmers can now be accomplished by students and startup teams with Python knowledge and determination to learn.

The learning curve is real - you need Python fundamentals, embedded concepts, and satellite domain knowledge. But it's achievable. Thousands of developers have made this journey, and the resources available today are better than ever.

Start with blinking LEDs. Progress to reading sensors. Build state machines. Implement telemetry systems. Before you know it, you'll be writing flight software for actual space missions.

The satellite industry needs programmers who understand both software and spacecraft. CircuitPython provides the bridge. Whether you're a student building your first CubeSat or a professional developing commercial satellite platforms, mastering CircuitPython opens doors to the rapidly expanding space economy.

The code you write could orbit Earth, collect crucial climate data, enable global communications, or demonstrate breakthrough technologies. That's the power of accessible space development - and CircuitPython makes it possible.

Ready to start your CircuitPython satellite programming journey? Get a development board, work through the tutorials, and join the community. The space industry is waiting for your contributions.