TinyGS: An Open Ground Station Network for CubeSat Communications

Introduction

TinyGS (short for "Tiny Ground Station") is an open, community-run network of satellite ground stations distributed worldwide, designed to democratize access to space communications. It was launched in 2019 under the name ESP32 Fossa GroundStation, originally as a weekend project to support the FossaSAT-1 LoRa satellite. The project's goal is to enable anyone to build a very low-cost ground station and join a global network that can receive telemetry from LoRa-based CubeSats and other transmitters. By leveraging inexpensive hardware and collaborative infrastructure, TinyGS lowers the barrier for small satellite missions - from university CubeSats to startup constellations - to downlink data via a ready-made network of volunteer stations. In essence, TinyGS provides a simpler, cost-effective alternative to traditional ground networks, helping space enthusiasts and developers "become a space pioneer - right from your backyard."

How TinyGS Works: Network Architecture and Automation

TinyGS's architecture consists of many independent ground stations (typically user-operated) that connect to a central cloud platform via the internet. Each station is a lightweight IoT-like device (an ESP32-based radio module with Wi-Fi) that listens for satellite signals and automatically forwards any received data packets to the TinyGS network server. The network itself orchestrates communications: when a supported satellite is overhead, the TinyGS network will automatically assign and configure nearby ground stations to tune to that satellite's frequency and settings. This autonomous "auto-tuning" means individual users do not need to schedule passes or manually point antennas; the system intelligently selects which satellite a station should listen to based on orbital proximity and network demand. As a result, the ground stations operate in a hands-off manner - continuously scanning and switching frequencies and modems as directed by the network.

On the backend, TinyGS combines what would traditionally be separate components (scheduling system, data archive, etc.) into one cohesive platform. All information about satellites, ground stations, and observations is contained in a single database, accessible through a web application, Telegram bot, or programmatic API. Whenever a TinyGS station captures a satellite's transmission, the data is automatically forwarded to the central database and becomes immediately available on the TinyGS web interface (which shows real-time packet feeds) and via a Telegram channel or bot notification. Satellite operators and hobbyists can thus retrieve their telemetry without needing direct access to each station - the network aggregates it for them. Conversely, if a satellite operator needs a specific station to focus on their satellite, they can disable the auto-tuning feature and manually configure that station for their target. However, by default the hands-free automation maximizes the chance that any satellite pass is heard by at least one ground node.

Notably, TinyGS ground stations typically use omnidirectional antennas (no tracking rotors) and do not require complex pointing hardware. This simplicity is by design - it trades the higher link margin of directional antennas for the sheer number of stations listening, and ease of deployment. To compensate for weak signal levels from orbit, station builders often add a low-noise amplifier (LNA) at the antenna input for better sensitivity. Even with a simple antenna, LoRa signals can be decoded at very low power (on the order of -120 dBm or below), which is one reason TinyGS can receive satellites using modest setups. Overall, the network's distributed nature (many stations worldwide) extends coverage - as a LEO satellite traverses the globe, different TinyGS nodes along its ground track will pick up its beacon in sequence, effectively increasing total contact time.

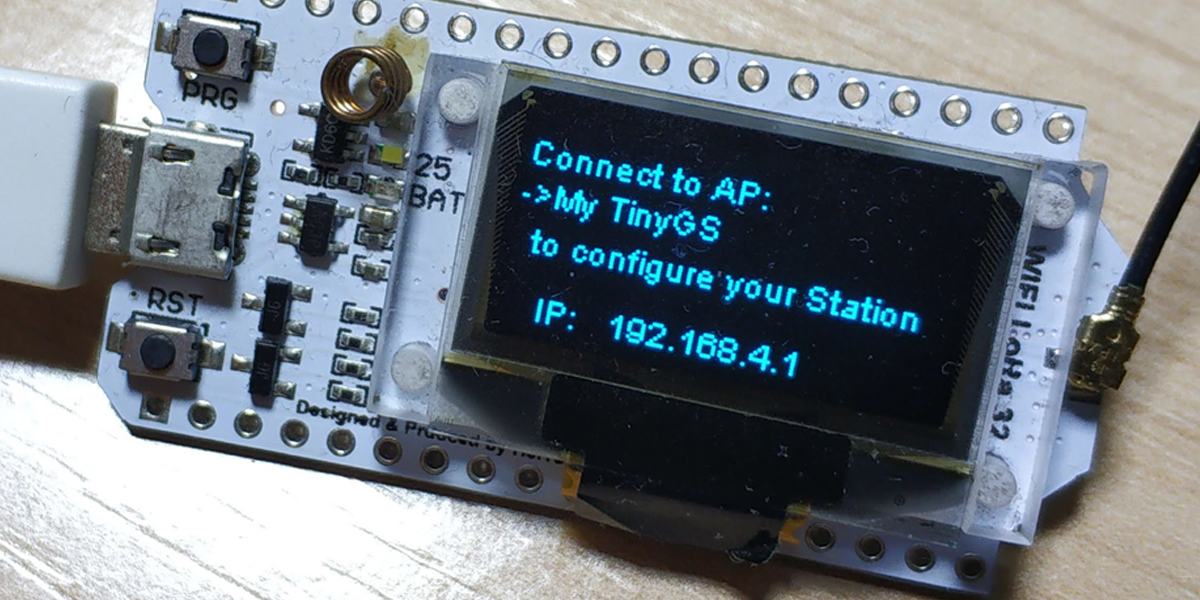

Another important aspect is that TinyGS firmware is built with internet connectivity and remote management in mind. Each station hosts a local web interface for configuration and supports over-the-air (OTA) updates of its firmware. In practice, this means the TinyGS team can push automatic updates to all stations to introduce new features or satellite decoders, and operators can adjust settings via a browser without physically accessing the hardware. These design choices (auto-tuning, OTA updates, etc.) make running a TinyGS station very low maintenance. Community members are further connected through a Telegram chat group where they can get support and discuss updates, reflecting the project's open and collaborative ethos.

Supported Ground Station Hardware

One of TinyGS's strengths is its use of cheap, readily available hardware. The project is built around the popular ESP32 microcontroller paired with Semtech LoRa radio transceivers (SX127x or SX126x families). Many off-the-shelf development boards combine these components, making it easy to assemble a station. According to the TinyGS documentation, any ESP32 board with an SX126x or SX127x LoRa module can be made to work, but the community has thoroughly tested and "officially" supports a number of specific boards for plug-and-play use. The table below summarizes the common hardware platforms supported by TinyGS:

Examples of TinyGS-Compatible Ground Station Hardware

Board / Device

LoRa Radio Chip

Frequency Bands

Heltec WiFi LoRa 32 (V1 & V2)

Semtech SX1276

433 MHz; 863-928 MHz

LilyGO TTGO LoRa32 (V1 & V2)

Semtech SX1276 / SX1278

433 MHz; 868-915 MHz

LilyGO TTGO T-Beam

Semtech SX1276

433 MHz; 868-915 MHz

FossaSat 1W Ground Station

Semtech SX1268

433 MHz; 868-915 MHz

Custom ESP32 + LoRa Module

SX1262 or SX127x

Varies (150-960 MHz)

Note: Boards are typically sold in either a 433 MHz variant or an 868/915 MHz variant (for EU or US ISM bands respectively). Some newer boards (e.g. Heltec V3 with SX1262) cover a wide tuning range. SX1262 chips can tune roughly 150-960 MHz, covering VHF and UHF; SX127x chips cover sub-GHz (e.g. 137-525 MHz for SX1278, or up to ~1020 MHz for SX1276 in some modes).

All of the above devices combine an ESP32 microcontroller (for Wi-Fi connectivity and control logic) with a long-range LoRa radio module. For example, the Heltec WiFi LoRa 32 V2 board is an ESP32 with an SX1276 LoRa transceiver and an OLED display for status; the TTGO T-Beam adds GPS and an SX1276; and the Fossa 1W GS is a custom unit capable of higher transmit power (1 W) for commanding satellites. Using these boards, enthusiasts can build a functional ground station for well under $50 - essentially just add a suitable antenna and power supply. The TinyGS firmware supports these boards out-of-the-box, and for custom combinations (e.g. an ESP32 dev kit wired to an SX127x module), the project provides template configurations to ensure compatibility. This flexibility means even a custom DIY setup can join TinyGS, as long as it uses the supported Semtech LoRa chipsets and an ESP32 to run the client software.

Radio Frequencies and Modulations Supported

TinyGS primarily targets Low-Earth-Orbit satellites transmitting in the sub-GHz UHF bands - most commonly the 433-438 MHz range used by amateur CubeSats. In fact, about 76% of TinyGS stations operate exclusively in the UHF band, since the majority of supported satellites use UHF frequencies. The network also accommodates other license-free industrial/scientific/medical (ISM) bands such as 868 MHz (Europe) and 915 MHz (Americas) when satellites choose those for downlinks. For example, some CubeSats from the VR3X mission broadcast around 903 MHz LoRa, which was within the US ISM band but in other regions landed in cellular spectrum. TinyGS station owners can select which band(s) their hardware covers, and many run multiple modules to cover both 433 MHz and 868/915 MHz bands for broader coverage. (A few stations even support VHF or S-band reception via additional equipment, though LoRa is rarely used there.)

On the modulation front, TinyGS is built around Semtech's LoRa technology, but it also supports several other modulation schemes that the LoRa chips can demodulate in hardware. According to the project's history, TinyGS was opened up "to any LoRa satellite" and expanded to support "other flying objects that have a compatible radio modulation with our hardware such as FSK, GFSK, MSK, GMSK, LoRa and OOK." In practice, the Semtech SX126x/SX127x family can be configured for straightforward narrowband FSK (frequency-shift keying) modes in addition to LoRa's chirp spread-spectrum mode. This means TinyGS stations are capable of receiving traditional FSK or OOK (on-off keying) transmissions, for example, some high-altitude balloon beacons or custom telemetry signals - provided they transmit in a supported frequency band and within the radio's bitrate limits. TinyGS's firmware uses the open-source RadioLib library under the hood to handle these modulation modes. A real-world example is the Norby 6U CubeSat, which alternated between LoRa and GFSK telemetry beacons; SatNOGS volunteers decoded its GFSK packets while TinyGS stations decoded its LoRa packets. (In theory TinyGS could decode both if future radios like the AX5243 are supported, which would allow open-source GFSK demodulation without proprietary LoRa constraints.)

It's important to note that LoRa, while technically proprietary, has become a popular choice for smallsats because of its robust link performance. LoRa modulation enables reliable, long-range links with very low power, at the cost of data rate. For tiny satellites sending telemetry or intermittent sensor data, this trade-off is often worthwhile: for instance, FossaSAT-1's LoRa beacon could be received at signal levels that would be impossible for many other protocols. However, the use of LoRa in space does raise regulatory considerations. Many LoRa satellites operate under amateur radio licenses in the 435 MHz band or use ISM bands, but frequencies that are "license-free" for low-power devices on the ground are not license-free in orbit. Satellite operators still must obtain a proper frequency coordination and license (often via the IARU if using amateur spectrum). For example, 434 MHz is a common downlink for CubeSats, but it isn't universally unlicensed worldwide, and ISM bands like 900 MHz are not allocated for space use without permission. The takeaway is that while TinyGS supports several modulation types and frequencies, missions should choose frequencies in accordance with regulations and consider regional differences (e.g. EU's 868 MHz vs US's 915 MHz). TinyGS's community and documentation often provide guidance on these aspects to new teams.

Using TinyGS to Downlink CubeSat Data

For satellite operators - whether a university CubeSat team or a commercial startup with a technology demonstrator - TinyGS offers a ready-made ground segment to collect your data. A satellite developer can add their satellite to the TinyGS network's database (through the TinyGS web interface or by contacting the project maintainers) and thereby enlist the global network of stations to listen for it. Once a satellite is marked as "supported" in TinyGS, the network will include it in the auto-scheduling logic: any time the satellite passes over an active ground station, the station will automatically tune to the satellite's frequency and attempt to demodulate its signal. This effectively crowdsources your downlink across hundreds of ears around the world. Data packets received by any TinyGS station are forwarded to the central database in real time, and the system tags them with the satellite's ID, the receiving station, timestamp, etc. An operator can log into the TinyGS web dashboard to view all packets (telemetry frames) coming from their satellite, or even watch live as packets arrive during a pass. TinyGS also provides an API for satellite owners to programmatically fetch their data, and a Telegram bot can push alerts or data for each packet if configured. In other words, TinyGS can function as a free, shared ground station network for downlinking telemetry - greatly simplifying early operations for resource-limited teams.

Several missions have successfully used TinyGS for their communications. Notably, the very first LoRa CubeSat, FossaSAT-1, relied on the (then nascent) TinyGS network in late 2019 - within days of its launch, a TinyGS station in Spain received the first LoRa packet from FossaSAT-1. The satellite's developers were able to gather their telemetry through community stations without deploying any dedicated ground infrastructure. Since then, numerous academic CubeSats have followed this model. A project can design its CubeSat's communications around a LoRa module (or compatible FSK transmitter) and immediately benefit from an existing community of ground stations. For example, a team might downlink health data or sensor readings at regular intervals, knowing that if any volunteer station picks it up, the data will appear on TinyGS for retrieval. This approach has been embraced by universities and even some commercial demo satellites because it de-risks the ground segment - there is less worry about missing a pass due to a single station's failure when dozens of stations are listening around the globe.

Of course, using TinyGS does come with considerations. Because it's an open network, all received data is openly visible on the TinyGS website (which is generally fine for telemetry or amateur experiments). And while the coverage is extensive, it is not guaranteed in the way a paid, contracted ground station network might be. Nonetheless, with over a thousand stations online (as of 2023), TinyGS can often rival or exceed the coverage of expensive alternatives, especially for low-throughput data like beacon packets. Satellite operators are encouraged to engage with the TinyGS community - for instance, via the Telegram support chat - to announce their mission and ensure their satellite's details (frequency, modulation, callsign, etc.) are correctly entered in the database. In return, they receive not only the technical service of data downlink, but also community goodwill and interest in their mission. This model has proven particularly valuable for educational satellites and research projects, where budgets are small and the primary goal is to collect some data and involve a community, rather than maintain proprietary communications.

PyCubed: CubeSat Platform with Native LoRa (TinyGS) Integration

One development that has boosted TinyGS's relevance is the emergence of CubeSat avionics platforms that incorporate LoRa radios. A prime example is PyCubed - an open-source, radiation-tested CubeSat hardware platform developed originally by researchers (the name hints at its Python-programmable nature). PyCubed integrates the satellite's power supply, onboard computer, and communications into a single compact board, and notably, it includes a HopeRF RFM98PW LoRa transceiver module as its communications radio. The RFM98PW is a high-power (1 W) LoRa module operating in the 433 MHz band, which gives a PyCubed-based satellite a robust downlink channel that aligns perfectly with TinyGS ground stations. In fact, PyCubed's designers chose the LoRa module for its turnkey long-range capabilities: as one developer explained, the RFM98W can do multiple modulations (FSK, GFSK, MSK, GMSK, LoRa, OOK) and using unlicensed bands could bypass some regulatory hurdles, "not to mention [enable] simple/cheap groundstations with similar hardware." In other words, a motivating factor was that a CubeSat with an RFM98 radio could utilize the same inexpensive devices on the ground (like ESP32 LoRa boards) as its receivers - exactly what TinyGS provides.

By adopting PyCubed, even relatively small teams can have an out-of-the-box communications solution that ties into TinyGS. The typical PyCubed board comes with the LoRa module pre-wired and software libraries to format telemetry. A satellite using it might transmit, say, a packet every 30 seconds at a certain spreading factor and frequency (e.g. SF10, 125 kHz bandwidth at 437.1 MHz). All the team needs to do is register that frequency and modulation with TinyGS, and immediately dozens of ground stations will be ready to receive those packets. Since PyCubed also runs higher-level software (it's often programmed in CircuitPython or C/C++), teams have integrated custom telemetry encodings or failsafes, but the underlying link is still LoRa - so TinyGS's standard decoders (or user-contributed decoders) can parse the data.

One mission that exemplified this is Stanford's set of V-R3x CubeSats (part of the VR3X/ViseR project), which used PyCubed-based hardware and LoRa radios. When they launched in January 2021, the TinyGS network was able to receive their beacon frames right away. This demonstrated the plug-and-play nature of PyCubed + TinyGS: the satellite's builders didn't have to erect a global station network; they tapped into the existing one. For university CubeSat projects, this is hugely advantageous. PyCubed provides the integrated flight electronics, and TinyGS provides the ground infrastructure - together covering major pieces of the mission for a fraction of typical cost. It's worth noting that PyCubed is open-source hardware, so variations of it exist (e.g. "PyCubed Mini" for smaller form-factors), but all share the common trait of an onboard Semtech-based LoRa transceiver. Thus, they all are natively compatible with TinyGS and can be used to quickly stand up an end-to-end CubeSat communication system.

Blackwing Space's ROOK: A PyCubed-Based OBC and TinyGS Compatibility

Building on the PyCubed concept, some startups have begun creating commercial-grade CubeSat buses that still leverage LoRa for communication. One notable example is Blackwing Space's ROOK onboard computer. The ROOK is essentially a ruggedized, improved version of the PyCubed architecture - it integrates the satellite command and data handling (C&DH), power management, and radio in one unit, and is designed for higher reliability in space (Blackwing has famously tested their hardware to survive extreme G-forces, as in the SpinLaunch suborbital tests). Despite its enhancements, ROOK remains fundamentally based on the PyCubed design, which means it includes a LoRa radio transceiver for comms. In effect, Blackwing Space adopted the PyCubed's approach of using an RFM98 (or similar Semtech chip) radio so that small satellites can use the readily accessible LoRa ecosystem for telemetry.

For TinyGS, the emergence of devices like ROOK is great news: it means even commercial CubeSats can directly interface with the TinyGS network if they choose LoRa for downlink. A Blackwing ROOK-equipped satellite can transmit its telemetry in the same format that TinyGS stations expect, ensuring that all those community ground stations will pick up the signals. Blackwing's goal with ROOK is to provide a flight-proven yet low-cost satellite platform (targeting startups and research teams who can't afford bespoke $50k radios). As such, they advertise compatibility with amateur band operation and the use of LoRa, which implies that a mission using ROOK can plan to utilize volunteer ground networks like TinyGS instead of (or in addition to) expensive dedicated ground sites. While specific documentation on ROOK's radio settings isn't public in detail, it's clear from its PyCubed heritage that if you build a satellite around ROOK, you'll be operating in the same LoRa/FSK frequencies, making it "TinyGS-ready" by default.

To illustrate, imagine a modern CubeSat using a ROOK OBC: it might broadcast a 0.1 kbps LoRa beacon on 437.5 MHz every minute with critical health data. Upon deployment, the satellite team could simply ensure TinyGS knows the satellite's NORAD ID and frequency, and then watch as telemetry is collected via TinyGS stations worldwide without needing to invest in any hardware on the ground. This capability is particularly attractive to newer space startups proving their technology - they can focus on the on-board experiment or payload, confident that basic communications and data retrieval can lean on an existing open infrastructure. It's a symbiotic relationship: TinyGS gains more interesting satellites to receive (thus engaging its community), and satellite developers get free downlink coverage. Blackwing's ROOK exemplifies this new class of CubeSat "plug-and-play" boards that effectively bridge the satellite-to-IoT gap, bringing space within reach of small teams. And because ROOK is sold commercially, it signals growing industry acceptance of using LoRa and networks like TinyGS even for professional missions.

Global Coverage, Community, and Scalability

In just a few years, TinyGS has grown into a very large distributed network. By mid-2023, TinyGS outpaced the older SatNOGS network in terms of active ground stations, boasting a higher number of online stations and a more globally distributed presence than SatNOGS. As of early 2024, TinyGS had on the order of 1,300 -1,500 active ground stations reporting in within a 24-hour period - an impressive scale for a community-driven project. These stations are spread across all continents, with particularly strong coverage in Europe and North America (where hobbyist activity is high) and growing presence in Asia, South America, and Africa. The wide geographic distribution means that many LEO satellites can be "seen" by at least one TinyGS node on most orbits, provided the satellite emits in the supported bands. In addition to station count, the network's user base has expanded into the thousands. By late 2023, TinyGS's social media reported over 4,800 members and millions of packets collected, reflecting how many individuals and institutions are participating. This large community acts as a support system and knowledge base for newcomers.

The TinyGS community is centered around open communication channels: a primary Telegram group (for general discussion and help), as well as dedicated Telegram channels that broadcast live packet receptions and station status updates. Enthusiasts can literally watch a feed of telemetry frames coming in from various satellites, fostering a sense of collaborative monitoring. The community also uses platforms like Twitter (X) and a GitHub repository for development. Volunteers contribute decoder modules for new satellites, improvements to firmware, and documentation translations. The spirit is very much one of sharing and learning - many station operators are radio amateurs, students, or citizen scientists eager to contribute to satellite missions. TinyGS also benefits from educational workshops and hackathons; for example, events like EMF Camp and local hacker spaces have run "Build your own TinyGS station" workshops, further spreading the word and increasing the station count. This grassroots growth is a virtuous cycle: more stations lead to better satellite coverage, which attracts more satellite projects to use TinyGS, which in turn attracts more volunteers to set up stations.

From a technical standpoint, the TinyGS network has shown it can scale well with this growth. The central server (and database) handles incoming data from hundreds of stations simultaneously, and the developers have implemented measures to manage bandwidth and prioritize traffic. The use of Telegram bots for data notifications is an ingenious way to leverage a scalable messaging platform for near-real-time data distribution without requiring every user to poll the database. Meanwhile, auto-tuning and remote updates ensure that even as new satellites come online or old ones go silent, the ground stations adapt swiftly. For instance, when a new LoRa satellite is added to the TinyGS database, stations in range will automatically begin listening for it - no need for each operator to manually update frequencies. If a bug is found in the firmware, the maintainers can push an OTA fix network-wide, often without users even noticing beyond a quick reboot of their node. This level of central coordination, combined with volunteer hardware, is what makes TinyGS unique.

Finally, it's worth highlighting that TinyGS's openness extends to data: all the packets collected are publicly available on the website (and via APIs). This can be incredibly useful for researchers who want to analyze smallsat telemetry or for tracking satellites' health by the community. Some participants simply enjoy the challenge of receiving space signals and contributing to something bigger. The project embodies the citizen-science approach to space operations, proving that with modern IoT technology and the internet, a crowdsourced ground station network is not only feasible but highly effective.

TinyGS vs. SatNOGS: A Brief Comparison

Both TinyGS and SatNOGS are prominent open-source ground station networks, but they differ significantly in design and scope. SatNOGS, started in 2014 by the Libre Space Foundation, uses software-defined radios (SDRs) and is tailored to decode a wide array of traditional amateur satellite signals (APRS, CW, BPSK, AX.25, FM voice, etc.). A typical SatNOGS station involves a Raspberry Pi, an SDR dongle, and often a rotator with directional antennas. By contrast, TinyGS focuses on LoRa and similar narrowband signals, using fixed, omnidirectional stations with commodity LoRa transceivers instead of general-purpose SDRs. This specialization makes TinyGS stations much cheaper and easier to set up - on the order of tens of dollars and an afternoon of work - whereas even a fixed SatNOGS station might cost a couple of hundred dollars (and a full rotator-equipped station much more). TinyGS's simplicity comes with the trade-off that it currently supports fewer types of signals: essentially those that the Semtech chips can handle. SatNOGS, using SDRs and a variety of decoders, has successfully received many more satellite missions (including high-speed data, imagery downlinks, etc.). In fact, as of mid-2023, SatNOGS had communicated with a larger number of distinct satellites overall - largely because many satellites use traditional modulations not covered by TinyGS.

Another key difference lies in how contacts are scheduled. SatNOGS relies on user scheduling: community members or satellite owners must plan observations through the network's interface, assigning a station to listen to a specific satellite at a specific pass. The station's client then executes the observation and uploads the results. TinyGS removes this manual step by using automated tuning: the network backend itself decides which satellite each station should be listening to at any given time, based on orbital predictions and station location. This means TinyGS stations are essentially always scanning for whichever satellite is available, without human intervention. The advantage is maximum automation and no missed opportunities (a pass will be caught as long as a station is nearby, even if nobody explicitly requested it). The disadvantage is less user control - unless one opts out of auto-tuning for a station, you can't pick a specific obscure satellite to track on TinyGS. SatNOGS, on the other hand, gives enthusiasts fine control to target specific signals, and has a rich database of decoder scripts for dozens of protocols, which TinyGS lacks. In summary, SatNOGS is broader in capability but heavier-weight, whereas TinyGS is narrow-focused but ultra-accessible. They complement each other in many ways: for instance, some satellite teams transmit both a LoRa beacon (for TinyGS) and a CW or GMSK beacon (for SatNOGS and ham operators), ensuring the widest coverage.

From a community perspective, TinyGS's growth (in station count) has been faster recently, likely due to the minimal setup and the buzz around LoRa satellites. SatNOGS remains very active as well, especially for traditional amateur radio satellite enthusiasts and for missions that need higher bandwidth downlinks or uplinks (TinyGS currently has limited uplink capability, while SatNOGS stations can and do transmit commands when licensed operators are involved). For a space startup or a university CubeSat team deciding on a ground network, the choice might not be one or the other: they can use both. TinyGS can serve as a continuous background listenership for simple telemetry, and SatNOGS can be used for more complex communication sessions or backup. Notably, the cost difference means TinyGS can easily scale out with your mission - you can even encourage supporters worldwide to set up new TinyGS stations for better coverage, something much harder to do with the more complex SatNOGS hardware.

Conclusion

TinyGS has proven to be an innovative approach to satellite communications, leveraging IoT technology and global volunteer participation to support space missions in a way that was nearly impossible just a decade ago. For space startups, academic teams, and researchers working on CubeSats, TinyGS offers an attractive strategic option: a readily accessible, zero-cost ground station network that can significantly ease the challenge of downlinking telemetry from orbit. By understanding TinyGS's architecture - its use of LoRa/FSK radios, automated network scheduling, and community-driven operations - mission planners can make informed decisions about incorporating it into their communications plan. A CubeSat equipped with a compatible radio (like those on PyCubed or ROOK boards) can essentially hitch a ride on this open network and start sending data home from day one, without a multi-million-dollar ground infrastructure. This democratization of the ground segment lowers the entry barrier for new space ventures and enables rapid iteration and testing in orbit.

Of course, TinyGS is not a panacea for all communications needs. Its bandwidth is limited (LoRa packets are small), and it relies on volunteer stations that come with no formal service guarantees. Missions with high data volume or critical commanding requirements will still need dedicated solutions. However, as a supplementary network and as a community-engagement tool, TinyGS is extremely valuable. It creates a direct link between satellite builders and a global audience of operators tuning in - a form of participatory space exploration. The network's ongoing expansion, and its integration with platforms like PyCubed, suggest that LoRa-based CubeSat comms will continue to grow in popularity. TinyGS is evolving alongside, with plans to support new radio chips and perhaps higher-frequency bands in the future.

In summary, TinyGS represents a convergence of the NewSpace ethos (moving fast and leveraging COTS components) with the open-source mindset. It enables even the tiniest satellites to speak to us across space, using the simplest of ground setups. For anyone planning a CubeSat mission today, it's worth considering TinyGS compatibility from the outset - it could save you time, money, and enable your satellite to be heard by an enthusiastic community of ground station operators around the world.